Study characteristics and LCS participation

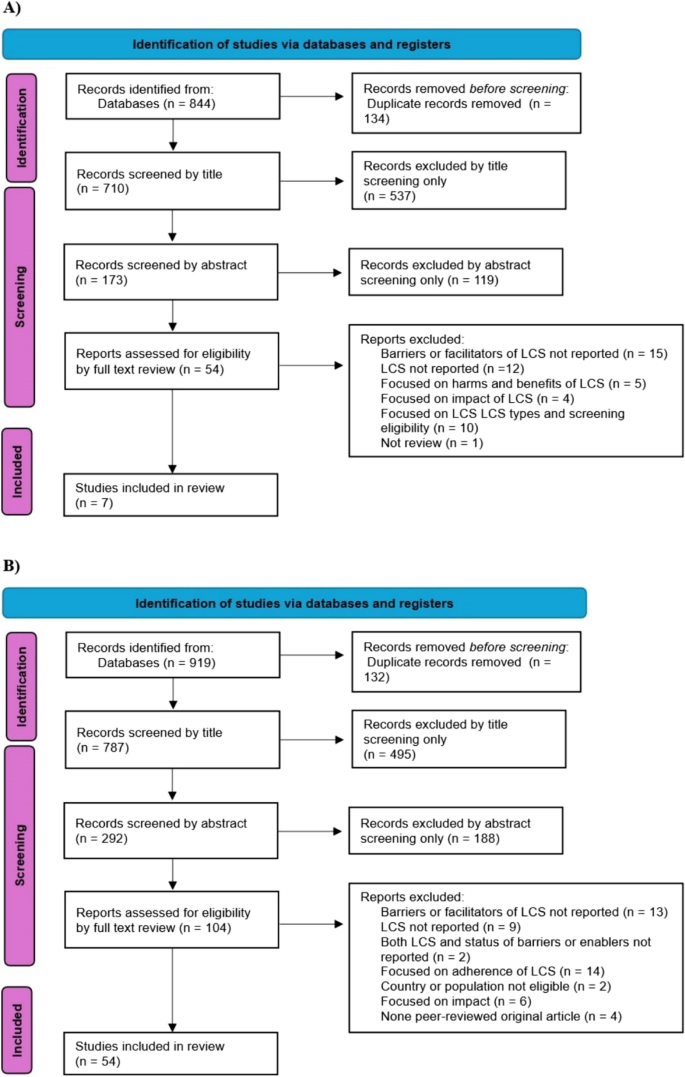

Over 110 million participants (110,999,150) were included across seven reviews (n = 2,988,779) (Table 1, Fig. 2A) and 54 recent and original research articles (n = 108,010,371) (Tables 2 and 3, Fig. 2B). Over half (n = 4) of the review articles included 20–40 original studies, published between 2001 and 2020. Over half (58%) of the original articles in the six reviews and nearly nine-tenths (87%) in the top-up systemic review were conducted in the USA (Tables 1, 2 and 3).

PRISMA flow diagram for study selection: A previous reviews for the umbrella review B recent articles for systematic review LCS = Lung Cancer Screening

The corrected covered area was calculated to be 3.23%, indicating minimal overlap among individual primary studies across the reviews included in the umbrella review.

Facilitators of LCS

Facilitators at the organizational, healthcare provider, or interpersonal, and individual levels enhance LCS participation. At the organisational-level (promotion of the program, trained staff, integration of LCS with other services, and supportive technology), healthcare provider level (information provision, clear screening recommendations, interest in training, and positive patient relationships), and individual level (experience with health services and awareness of cancer). The section below presents the facilitators of LCS (Supplementary 1 − Table S2B, Fig. 3A).

The barriers and facilitators of lung cancer screening: A Facilitators B Barriers. EHR = Electronic Health Records, HCP = Healthcare Provider, LCS = Lung cancer screening

Organisational or policy-level facilitators

System readiness and embedding technology

System readiness facilitates LCS participation. This involves resource allocation, dedicated staff, established screening workflows, decision aids, streamlined referral processes, template for screening referral and documentation, concise guideline summaries in a suitable format, insurance codes, leadership support, staff engagement, and nursing navigators involvement [16, 23, 25, 50, 70, 74, 77]. Screening rates were higher in programs providing transportation to LDCT locations or covering transportation costs [25], one study noted a 43% increase in intention to participate when individuals had convenient access to the cancer screening unit [16]. Facilities with breathing centres (specialised units for managing respiratory health and conditions) and those meeting high standards, like the US National Lung Cancer Screening Test standard saw better participation rates (OR 1.48, 95% CI: 0.92–2.38) [23]. Integrating LCS with routine visits, such as wellness or acute care visits, improved participation rates [73]. Health systems with supportive and knowledgeable leaders who actively engage, and train staff also reported higher screening participation [16, 25, 74] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2B, Fig. 3A).

According to findings from a previous review [16] and recent articles [44, 46, 62, 69, 74], the use of technology-assisted LCS ─ such as Electronic Health records (EHRs), notification systems, and reminders ─ has been shown to substantially enhance LCS rates [46, 62]. 65% of US healthcare providers indicated that EHRs provided hints about screening eligibility [74] and positively influenced their likelihood to refer patients for LCS [46]. Specifically, services that used EHRs prompts compared to those without were more likely to identify eligible patients for LCS (adjusted odds ratio (aOR); 1.59, 95% CI: 1.38–1.82), refer to LDCT (aOR 1.04, 95% CI: 1.01–1.07), and complete LDCT criteria documentation (aOR 1.19, 95% CI: 1.15–1.23) [44] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2B, Fig. 3A).

Health education and advertisement

Individuals who were referred for LCS or had it, recommended, or endorsed by healthcare providers, family, or other organisations, such as professional associations, increased screening participation [22, 25]. US community health workers played a key role in raising awareness and referring individuals to LCS [72].

Advertising to promote and raise awareness of LCS generally and LCS programs specifically also increased participation [28, 35, 70, 72]. For example, 15.5% of individuals in the USA cited mail advertisements for attending LCS [35]. Advertising LCS programs, which inherently includes raising awareness about LDCT, combined with providing free screening in the USA increased screening volume from an average of 4.6 patients per month during the fee-based period (10 months) to 66.0 patients per month during the free period using targeted advertisements (billboards, TV and radio, interviews, direct mailings, newspapers) and primary care outreach (10 months) [28]. Healthcare providers highlighted the value of promoting LCS through social media (presenting case studies in the news), EHRs, patient waiting rooms, or community settings [70].

Cultural acceptance, trust, and discussion

Cultural acceptance of LCS and strong family values were identified as key facilitators of LCS participation [16], alongside positive experiences with staff and appointments, and trust in the healthcare providers [16, 22]. US participants highlighted the importance of cultural safety in LCS, including supporting family decision-making by communicating with and providing information to eligible individuals that enable family discussions, for example, by sending a letter (“You send a letter, his family also reads it.his family members will encourage him to go”) [72]. Most participants expressed a preference for healthcare providers who share a similar cultural background and speak their language. For providers who do not, they emphasize the need for interpretation services, particularly when dialects differ [72].

Healthcare provider-patient or interpersonal-level facilitators

Positive communication and recommendations

Higher LCS participation was noted among individuals who received LCS recommendations or information from healthcare providers or community members [16, 29, 32, 35, 50, 55, 75]. For example, a review documented that individuals recommended for screening by healthcare providers were 2.6 times more likely to participate [16]. Common motivators for LCS participation in the USA included recommendations from Community Health Advisors (68.9%), friends (27.6%), family (15.5%), doctors (3.4%), or others (5.2%) [35]. In Canada, supportive, collaborative relationships with healthcare providers were linked to higher LCS participation [75]. In China, 62.4% of individuals reported being counselled for screening by their doctors [32] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2B, Fig. 3A).

Knowledge, perception, and experience

Healthcare providers were more likely to refer and screen patients if they trusted the scientific evidence supporting LCS guidelines and believed LCS to be cost-effective and beneficial [25]. LCS implementation was greater among providers who felt confident discussing its pros and cons with patients [16, 25], had adequate time for counselling the screening process and outcome [25] and could utilize EHRs for screening and referral [25] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2B, Fig. 3A).

Individual-level facilitators

Awareness and trust in LCS

Awareness of LCS and insurance cost coverage and knowledge of the benefits of screening were associated with higher participation in a review conducted in the USA [25]. Those who perceived the benefits of LCS to outweigh associated risks, trusted the accuracy of LDCT, and viewed LDCT as convenient, were more likely to participate [22, 25]. For example, in the USA, individuals perceiving a benefit from LCS were twice as likely to participate (P = 0.01). Most participants in this study felt the benefits outweighed the risks, with some patients (< 50%) raising concerns about screening effectiveness [22].

Chronic disease, cancer, and healthcare system experience

Experience with chronic disease and cancer and regular interactions with the healthcare system was associated with increased participation in LCS programs, potentially due to higher levels of awareness of the benefits of screening, the procedures involved, and clinical pathways. Individuals with existing chronic medical conditions (referred to as comorbidity) had up to a twofold LCS participation rate. For example, the LCS rate was higher among eligible individuals in the USA with ≥ 3 comorbidities compared to those without comorbidities (aOR 95% CI: 2.38 (1.48–3.83)) [52]. Additionally, eligible Americans who rated their general health as poor (aOR: 1.68 (1.35–2.10)) or fair (aOR: 1.35 (1.12–1.62)) had higher participation rates than those who rated their health as excellent, very good, or good [55] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2B, Fig. 3A).

Individuals with a close relative or friend diagnosed with cancer have better LCS participation [13, 16, 25, 35]. In China, LCS rates increased with the number of family members with cancer: one (aOR 95% CI: 1.88 (1.80–1.96)), two (2.65 (2.51–2.79)), three (2.83 (2.64–3.04)), and four or more (3.46 (3.15–3.79)) [13]. In the USA, 19% of individuals reported that knowing someone with cancer influenced their decision to participate in LCS [35].

LCS participation rates are higher in individuals who receive regular health check-ups or have visited health facilities [16, 50, 55, 62, 75]. Those who routinely underwent health check-ups were 2.9 times more likely to participate in LCS [16]. Each additional health facility visit was associated with a 10% increase in LCS participation (aOR; 95%CI: 1.10 (1.07–1.13)) [62].

Prioritising health and perceived susceptibility

Individuals were motivated to undergo screening by wanting to seek reassurance of good lung health, maintain a health-conscious mindset, monitor their health, and reduce worries about lung cancer. Some wanted to ‘see the state of their lungs’ to evaluate lifestyle changes or consider smoking cessation [16, 22]. Moreover, in the USA, LCS participation was 63% higher among individuals who perceived themselves as susceptible to lung cancer than those who did not [16].

Barriers to lung cancer screening

LCS participation is influenced by factors at the organizational, healthcare provider or interpersonal and individual levels. At the organisational-level (reduced service access, limited health insurance and inadequate workforce, communication, information resources, and technology to support the program), healthcare provider level (limited LCS knowledge and training, sub-optimal referral processes, limited knowledge about the cost coverage by health insurance, and time limitations), and individual level (low awareness about LCS and its cost coverage by health insurance, fear of being diagnosed with cancer or the screening process, doubts about effectiveness, low interest, and time constraints). See supplementary 1 − Table S2A and Fig. 3B for further details.

Organisational or policy-level barriers

Infrastructure and access

Previous reviews [16, 27] and recent articles [68, 71,72,73, 77] highlight the limited infrastructure for LCS. Key challenges include low system readiness, insufficient health information technology (including a lack of EHRs or restricted ability to use electronic records to determine LCS eligibility (i.e., smoking pack-years), and send communications including invitations, reminders, and results notifications), decision aids, training materials, and limited scientific evidence supporting the LCSPs [16, 25, 71, 73, 77]. High staff turnover, shortage of multidisciplinary teams or trained personnel, absence of dedicated screening counsellors, and limited leadership support were also reported as barriers to access and therefore participation in LCS programs [16, 25, 74, 77]. Barriers in the USA included insufficient resources, such as patient educational materials, patient transportation, physical space, and supportive care throughout screening [68, 72]. Additionally, aspects of LDCT, such as the large, cylindrical shape of the machine and the perceived invasiveness of the procedure, were thought to induce anxiety or fear of tight or enclosed spaces (claustrophobia) representing test-related barriers that influence LCS participation [16, 46, 68, 69, 71, 73] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2A, Fig. 3B).

Geographic access also impacts LCS participation, with lower screening rates in rural compared with urban areas, as reported in both reviews [16, 22, 27] and recent articles [30, 31, 33, 38, 42, 43, 48, 50, 53, 55, 61, 62, 69]. In the USA, rural (aOR; 0.12, 95% CI: 0.04–0.37) and sub-urban (aOR 0.56, 95% CI: 0.31–0.99) facilities had lower LCS rates than urban centres [62]. In China, top-ranked facilities were more likely to offer LCS, reflecting disparities with respect to infrastructure and workforce [48].

Financial difficulty and health insurance

The reviews [16, 22, 25, 27] and recent articles [11, 37, 38, 50, 52, 55, 62, 63, 66, 68, 71, 74, 75] identified limited health insurance and financial barriers to LCS. Challenges include health insurance policies that do not cover screening costs, delayed reimbursements, low payments, lack of coverage for follow-up screening, and complex authorisation processes such as lack of automatic approval. Claim errors often delay healthcare provider reimbursement [25, 74]. In a previous review, 25 − 33% of individuals cited lack of insurance as a main reason for not screening [27]. In the USA, LCS rates were 0.43 times lower among uninsured compared to insured individuals (aOR 0.43, 95% CI: 0.26–0.70) [55], while uninsured Chinese individuals were 0.23 times lower compared to those insured (aOR 0.23, 95% CI: 0.10–0.53)) [11].

Other financial barriers to LCS participation include difficulty covering medical expenses, concerns about additional (non-medical) costs (e.g., transportation), and potential treatment costs if diagnosed with cancer. LCS rates were 0.52 times lower among individuals who were unable to afford care in the past year than those without such financial challenges (aOR 0.52, 95% CI: 0.39–0.70) [55].

Inadequate communication and mistrust

The reviews [16, 25] and recent articles [49, 62] identified low LCS participation rates in individuals facing communication and language barriers that made navigating the screening procedure difficult. A USA study found that only 3% (7/257) of LCS websites provided information in languages other than English [49]. Medical institutions and news sources providing LCS information often focused on screening benefits (85%) and lacked key details, such as eligibility criteria (38%), associated risks (36%), and screening process information (27%) [57].

Mistrust in the health system also contributes to low LCS participation, as identified in previous reviews [16, 22, 25, 27] and recent articles [68, 75]. Mistrust generally refers to a lack of confidence that develops over time due to systemic issues or a perceived lack of cultural safety, whereas distrust implies a more active suspicion or belief that the health system may cause harm. Both sentiments can lead individuals to avoid preventive services such as LDCT screening [94]. Distrust—stemming from negative experiences or loss was particularly impactful among minority populations [16, 22, 27]. In Canada, individuals cited the judgment or insensitivity of healthcare providers as a barrier to LCS [75].

Regulation and policy

LCS rates were significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, with declines observed during lockdowns [45] or seasonal infection peaks [36, 64]. In the USA, the LCS rate dropped by 29.6% during the lockdown, from 37.4% (pre-pandemic) to 16.5% (pandemic, P < 0.001) [45]. Post-March 2020, LCS rates fell by 0.54 times compared with pre-pandemic levels (Incidence Rate Ratio (IRR) 0.54, 95% CI: 0.33–0.89) [64] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2A, Fig. 3B).

Regulatory barriers to LCS include requirements for separate appointments for screening decisions, mandatory paperwork, restrictions allowing only pulmonologists to order screenings, and insurance prerequisites like prior authorisation [16, 25]. The lack of reassurance about screening outcomes and the absence of immediate intervention guarantees for lung cancer or incidental findings further reduce participation [25].

Multiple and evolving LCS guidelines and eligibility criteria complicate the screening process. Screening reporting metrics were also often inconsistent [69, 70]. Over half (52%) of US primary care providers reported the “vague” screening criteria challenged their practice [46], such as conflicting age limits from USPSTF and Medicare (88 vs. 77 years, respectively) [46]. Calculating smoking pack years was also seen as complex [46].

Previous reviews [14, 23] and recent articles [15, 23, 29, 69, 72] noted a lack of organisational culture to make LCS routine, with some patients not recalling being offered to screen [16, 69]. A USA review found that more than half of high-risk smokers were not recommended for LCS [27].

Community belief and stigma

Community-level social, cultural, and religious beliefs (e.g., viewing lung cancer as untreatable or believing that screening cannot help or “provide a new pair of lungs”), along with low collective acceptance of LCS and widespread lung cancer stigma (e.g., blame, social isolation, shame, mistreatment) are reported barriers to participation [16, 22, 25, 27, 69, 71] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2A, Fig. 3B).

Healthcare provider-patient or interpersonal-level barriers

Awareness, perception, and experience

Healthcare providers’ limited awareness and experience of LCS have been documented in reviews [16, 25, 27] and recent articles [34, 41, 46, 48, 68, 71, 73, 74]. Some providers doubted the LCS evidence base, including the benefits, and were concerned about high false-positive rates, unnecessary radiation exposure, and psychological stress [34, 73]. Many providers lacked awareness of lung cancer risk factors and screening protocols [27, 34, 68], including how to identify and refer eligible patients, the location of LDCT facilities, and screening guidelines [16, 27, 34]. Limited familiarity with patient needs, documentation, referral process technology, and handling positive screening cases was also noted [16, 25, 34, 69, 73]. Some were uncertain about responsibility for patient follow-ups, abnormal results, and coordinating treatment if screened individuals were diagnosed with lung cancer [70].

Providers also had limited knowledge regarding the funding for LCS, including how screening costs are covered by insurance, the proper coding and billing of LCS appointments, and the specifics of screening guidelines [16, 25, 46, 74]. In the USA, health professionals have limited knowledge about LCSP guidelines, with 26% of primary healthcare providers unaware of LDCT, and inconsistencies with the United States Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines led to a discordant screening rate of 1.9%, with physicians often referring ineligible patients with a family history of lung cancer [46, 60, 76]. Screening practices vary widely, with some providers never recommending or referring patients for LCS, while others routinely offer it [27, 69].

Time constraints and limited motivation

Previous reviews [25, 27] and recent articles [68, 69, 72, 74] highlight the time constraints on healthcare providers when discussing the screening process, suggesting screening programs do not allocate enough time to parallels that are required to identify and refer eligible individuals [27, 68, 69, 74]. Healthcare providers reported limited time for tasks such as identifying, referring, screening, notifying results, counselling, and managing competing priorities [25, 27]. Difficulties coordinating the screening process, lack of market-competitive reimbursement from the government and/or organization, and income loss due to patient no-shows lead to low motivation to offer LCS [69]. Scheduling appointments is further complicated by the need for frequent, long-term patient contact [16, 25, 71] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2A, Fig. 3B).

Individual-level barriers

Awareness, belief, and psychological factors

Previous reviews [16, 22, 25, 27] and recent articles [29, 32, 48, 69, 70, 72, 73] reported that low awareness about lung cancer and screening remains a significant barrier. Many individuals lack knowledge about lung cancer, its risk factors, and the specifics of LCS (e.g., the process, locations, and insurance coverage). This leaves individuals uninformed, or confused about LCS, with some unable to describe the screening process [22, 27, 29, 68, 72]. For example, in a 2022 study, only 22.9% of Chinese respondents were aware of early lung cancer detection via LDCT [48]. Similarly, migrant Chinese livery drivers in the USA had never heard of LCS, nor were they aware of insurance coverage for it [72]. Negative attitudes toward LCS and doubts about its benefits also represent barriers [22, 27, 69]. Factors such as low interest, perceived inconvenience, and skepticism about LCS effectiveness led some to resist participation [22, 25, 69]. Individuals who feel healthy, lack symptoms, or do not perceive themselves at risk are more likely to dismiss screening as unnecessary [22, 25]. Additionally, LCS participation was 0.24 times lower among those with fatalistic beliefs (e.g., not wanting to know cancer status, P = 0.002) [16]. As one participant noted, “If God wants me to go, I’ll go” [69].

Both previous reviews [16, 27] and recent articles [32, 46, 68, 69, 73] identify that psychological factors like stress, anxiety, and fear of screening or cancer diagnosis further hinder participation. Concerns include false positives, radiation exposure, results waiting times, and the implications of incidental findings, such as follow-up tests or treatments [16, 32, 46, 68, 69, 71, 73]. In one review, 33% of individuals cited fear of diagnosis or radiation as reasons for avoiding screening (OR = 0.10, P < 0.001) [27] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2A, Fig. 3B).

Time constraints and competing issues

Reviews [16, 22, 25, 27] and recent articles [32, 43, 68, 71, 72] identified a lack of time, scheduling conflicts, competing priorities, and caregiving responsibilities as barriers to LCS. Participants talked about the time it took for different stages of the screening, such as travel time and time to complete the scan, and talked about the difficulty and cost of trying to fit this around work [27, 32, 43, 68, 71, 72] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2A, Fig. 3B).

Other and unclear findings

The reviews and recent articles found inconsistent relationships between LCS and factors such as individuals’ age, sex, race/ethnicity, smoking, education, and healthcare providers’ characteristics, including age, specialty, race/ethnicity, and year of service (Supplementary 1 − Table S2C). Some studies found that LCS rates increase with age [13, 14, 16, 23, 31, 40, 50, 52, 62, 63, 66], while others showed a decrease [38] or no significant relationship [11, 12, 37]. Most studies found no significant LCS differences between the sexes [11, 12, 27, 37, 51, 55, 63], though some indicated lower participation among women [38, 62, 66] or men [13].

One previous review [16] and some recent articles [27, 31, 37, 38, 41, 50, 66] reported generally lower LCS participation among minority races/ethnicities. However, other recent studies found that these differences were often not statistically significant [11, 12, 51, 52, 55, 62, 63] and previous reviews reached no conclusive findings on this issue [24, 26, 27]. Higher educational achievement was related to increased LCS participation in most of the previous reviews [16, 25, 26] and recent articles [13, 55, 66], though some found no significant variation by education [11, 37, 52].

Some studies found LDCT orders were higher among healthcare providers [25, 59] aged 40–49 years (P = 0.03), of Asian race/ethnicity (P = 0.02), and with internal medicine specialty (P = 0.002). However, other studies found no significant differences in LCS ordering by provider age, race/ethnicity, specialty, or graduation year [59, 62] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2C).

Age

Both previous reviews [16, 23, 27] and recent articles [11,12,13,14, 31, 37, 38, 40, 41, 50, 52, 62, 63, 66] have found an inconsistent relationships between age and LCS. Some studies found an increasing rate of LCS as age increased [13, 14, 16, 23, 31, 40, 50, 52, 62, 63, 66], while others found decreasing rate of LCS [38, 41] or no significant relationships [11, 12, 37]. For instance, a review by Huang and colleagues revealed that increasing age was related to an increase in LCS rate, with individuals aged ≥ 50 years had 1.94 times higher LCS rate than individuals aged < 50 years (OR, 95% CI; 1.94(1.52–2.49)) [23]. Compared to Chinese individuals aged 40–44 years, LCS rate was higher in those aged 45–49 years (aOR, 95% CI; 1.09(1.02–1.17)), 50–54 years (1.18(1.10–1.27)), 55–59 years (1.24(1.15–1.33)), 60–64 years (1.28(1.19–1.37)) or 65–69 years (1.30(1.20–1.40)) [13]. In USA, the proportion of LCS was higher among individuals aged 65–79 years (19.2%) than those aged 55–64 years (15.2%p = 0.04) [52].

Race

A previous review [16] and recent articles [27, 31, 37, 38, 41, 50, 66] and found that LCS participation was lower in minority races/ethnicities, while the difference was not significant in most of the recent articles [11, 12, 51, 52, 55, 62, 63] and no conclusive results have been reported in the previous reviews [24, 26, 27]. For example, a previous meta-analysis of five studies found that among eligible individuals, LCS rates were 57% lower among Black people compared to White people (OR: 0.43, 95% CI: 0.25–0.74). However, in four studies, LCS completion rates after referral did not significantly differ between Black and White individuals (OR: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.74–1.19) [24]. Similarly, the LCS rate was 0.52 times lower among Black Americans (aOR: 0.52, 95% CI: 0.28–0.96) than Whites [66]. LCS rate among individuals with Medicare insurance plans in the USA was lower in other race/ethnicity cohorts (1.7%) or non-Hispanic Black people (2.2%) compared to non-Hispanic Whites (3.7%) [38]. Despite lower rates of LCS observed among non-Whites, the variation was not significant (aOR 95%CI: 0.83(0.66–1.05)) [55].

Sex

Most of the previous reviews [16, 23, 27] as well as recent articles [11,12,13, 37, 38, 51, 55, 62, 63, 66] found inconsistent relationships between sex and LCS, with the majority of studies finding the lack of differences between men and women [11, 12, 27, 37, 51, 55, 63]. A lower rate of screening participation among women was found in some studies [38, 62, 66], whereas other studies found a lower screening participation among men [13] or no significant variations [11, 12, 27, 37, 51, 55, 63]. For instance, the LCS rate was 59% higher among Chinese women (aOR 95%CI: (1.59, 1.47–1.72)) than among men [13]. In the USA, the screening rate of men was 27% higher than women [62]. In the previous review, LCS rate did not differ between females and males, both in the total population (OR 95% CI: 1.18 (0.96–1.44)) or high-risk population group (OR 95% CI: 0.68 (0.42–1.10)); however, females have 32% times (OR 95% CI: 1.32 (1.15–1.52)) more LCS participation rate in the general population group (excluding high-risk group) [23].

Education

Higher educational achievement was related to increased LCS participation in most of the previous reviews [16, 25, 26] and recent articles [13, 55, 66], while some studies found a decreasing rate of screening among individuals with higher educational achievement [55] or no significant difference by educational status [11, 37, 52]. For instance, the LCS rate was 28% higher among Chinese individuals who completed undergraduate or above educational level (aOR 95%CI: 1.28(1.20–1.36)) compared to primary school or below educational attainment [13]. Individuals who attended college in North America have about two times higher LCS rates (aOR:1.84, 95% CI; 1.07–3.15) compared to those who completed high school or below [66]. Nevertheless, the LCS rate was higher among USA individuals who completed high school or less (aOR 95%CI: 1.25(1.07–1.46)) than those who completed college or higher education [55].

Smoking

There is a lack of consistency regarding the relationship between smoking and LCS participation. Some recent articles found a variation in LCS participation across smoking status [13, 41, 50, 66], while previous reviews [23, 25, 27] and some recent articles did not find variations by smoking status [37, 40, 63]; an inconsistent finding also reported by a previous review [16]. For example, in China, compared to never-smokers, screening participation was higher among former smokers (aOR 95%CI: 1.18(1.06–1.32)), while it was lower among current smokers (0.89(0.82–0.97)) [13]. In USA, the LCS rate was about twofold among individuals who attempted to quit smoking (aOR 95%CI: 1.77 (1.17–2.67)) [66]. In the previous review, smoking as a barrier was reported by two included studies, while one included study reported that smoking was related to increased LCS participation [16].

Characteristics of healthcare providers

There is inconsistent evidence regarding the variation of LCS by healthcare providers characteristics [25, 59, 62]. Ordering of LCS service varied by the characteristics of healthcare providers, such as age (p = 0.03), race (p = 0.02) and medical speciality (p = 0.002). For instance, total LDCT orders were higher among healthcare providers [25, 59] aged 40–49 years (32%), Asian race (32%), and with internal medicine speciality (40%). However, LDCT ordering was not varied across healthcare providers’ gender (p = 0.24), professional degree type (p = 0.12) or the status of having international graduate (p = 0.07) [59]. Another study also found a lack of variations of LCS ordering by the healthcare providers’ age, speciality, year of graduation and race/ethnicity [62].

Quality appraisal of included studies and reviews

Four reviews fulfilled 10 or more of 11 JBI critical appraisal criteria, with two of these achieving full scores (Supplementary 1 − Table S3). All reviews presented clear research questions and inclusion criteria, and identified study gaps; however, some lacked clear search strategies, appraisal criteria, and publication bias assessment. According to the MMAT, 38 recent articles met all criteria, while 13 had one or more “no” or “can’t tell” scores, and three were ineligible for detailed appraisal. Low scores were primarily because of non-representative sample sizes, uncertain sampling strategies, and high non-response rates (Supplementary 2).

link