Lexicographic qualitative approach of nurse’s perspectives on men’s access to sexual health care in Portugal

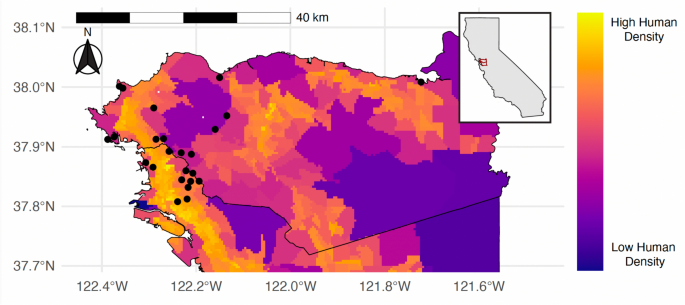

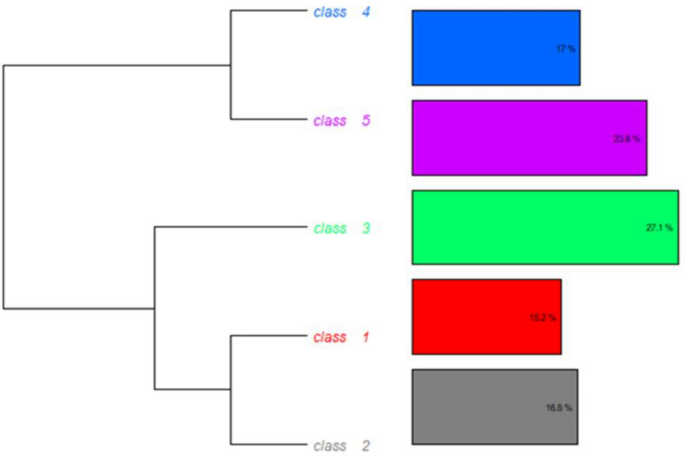

This study aimed to explore nurses’ perspectives on men’s sexual healthcare access in Portugal. As a result, our discussion will be organised by the analysis classes that emerged.

Class 1—approach triggers between nurses and men

Persson et al.21, supported by several studies, consider that men’s access to sexual health services is low and that they characterise this kind of service as heteronormative and “tailored for women”. These authors also noted that professional discourses often portrayed men as reluctant patients (2023).

Nurses and specialist nurses participating in our FGs mention acute health conditions as triggers to men’s access to sexual health care. Nurses’ discourses, interactions, and practices play an important role in reinforcing and reproducing gendered inequalities in sexual health care access. Our participants state that sexual health has traditionally been regarded as a women’s issue in Portugal and that these kinds of health services are characterised by scenarios populated by lay and expert women that exclude men and emphasise reproductive priorities.

Persson et al.21 stated that there is a growing global awareness that men should be included in sexual and reproductive programs and services, when considering information, counselling, testing, and treatment regarding sexually transmitted infections, unwanted pregnancies, sexual violence, and treatment of sexual dysfunction. Nevertheless, in Portugal, health policies still reinforce reproductive health as the focus and heterosexual women as the healthcare subjects. Tereso et al.25, as well as Persson et al.20, found that a lack of health professional training seems to be a barrier to men´s access to these kinds of services. In Portuguese nurses’ education (bachelor’s, professional specialisation, or master’s), sexual health, and specifically men’s sexual health, is not deepened and does not have visibility in syllabus contents. According to Persson et al.21, “The lack of a shared approach to men’s sexual health, and the absence of a professional discourse, indicate that training on men’s sexual health and masculinity is missing from education. This could explain why Health Care Professionals’ discourses on masculinity in Sexual Health Care were formulated about women and femininity as norms, and their private attitudes towards men and masculinity. A shared, knowledge-based discourse could enable a more consistent and shared approach to men in SHC.” (p.11)

In our study, participants also highlighted older nurses as chosen professionals for men to address their sexual problems, with whom they seem to be more at ease. The specificities related to men’s hospitalisation were also mentioned. Nurses’ perspectives on hospital units as spaces that do not promote privacy suggest that men prefer to address this kind of issue with doctors in their offices. Another important aspect is that men seek a curative approach, and as such, the need for a prescription or intervention makes physicians the professionals most valued by men.

Class 2—therapeutic itineraries singularities

When we endorse sexual rights, it is important to consider that they “protect all people’s rights to fulfil and express their sexuality and enjoy sexual health, with due regard for the rights of others and within a framework of protection against discrimination” (28, p. 3). Within this framework, male exclusion from sexual and reproductive healthcare in Portugal raises questions about men’s exercise of sexual rights and the challenges that nurses seem to be facing.

Our participants in the FGs mentioned that in primary health care, physicians do not seem comfortable approaching sexual issues. Typically, they refer patients to urologists without proper data collection and thorough problem assessment. Nurses’ perspectives of men’s therapeutic itineraries highlighted that physicians pass the problem on to someone else and seem to postpone the answer to men’s needs. In these settings, psychological aspects are usually undervalued, and the clinical evaluation focuses mainly on mechanical aspects related to sexual function or epidemiological concerns related to STIs.

Searching for help in an acute sexual condition takes older men to emergency services as a gateway to entering national health services. In these settings, their intimacy is sometimes not assured, which presents a significant challenge for them to disclose their problems.

Generally, our participants considered that access to and utilisation of sexual health services is easier for young men who benefited from sexual and reproductive information in schools and have more familiarity with nurses and fewer taboos to ask questions or approach this kind of issue. Digital resources were also pointed out as facilitators in seeking help when problems arise.

Sexually transmitted infections were mentioned as a complex issue to address with men because of their fear of being criticised or of moral judgments by nurses. Additionally, cultural issues related to the social perception of masculinity and the expectations of maintaining that image are considered barriers for men to seek help. Being sick translates into a state of weakness and vulnerability, which does not align with the social representations of being a man5. In the second FG, the critical issue of hegemonic masculinity beliefs emphasises men’s sexual performance and their need to prove that they are always ready to have sex. According to Courtenay5, social and institutional structures help to sustain and reproduce men’s health risks and the social construction of men as the stronger sex. These kinds of beliefs were considered a barrier for men to ask questions when sexual problems arise, especially in the case of homosexual or transgender men. Informal norms of masculinities seem to contribute to reinforcing male exclusion from sexual and reproductive healthcare as care subjects4.

Globally, there is a scarcity of research conducted to understand healthcare workers’ perspectives on factors affecting men’s utilisation of sexual and reproductive healthcare services, with the majority focusing on women and adolescents as subjects16. In our research, some specialist nurses emphasised the need for an opportunistic approach to addressing men’s sexual and reproductive aspects in maternal health consultations during pregnancy.

Class 3—sexual health as a subject

About this class, the difficulty of considering sexual health as a subject for men and nurses emerged. According to Klaeson et al.11, sexual health is a concept pervaded by taboos, and scientific evidence points out that nurses feel uncomfortable talking to patients about it and therefore avoid it. These authors state that this absence forms an obstacle for nurses to promote satisfactory sexual health care to patients in general.

In our data analysis, nurses who approach sexual health in their clinical practice are perceived by their colleagues as those who have made a personal investment in developing knowledge and professional experience. Generally, older nurses are considered the best equipped to tackle the subject and are seen as the informal trainers of younger nurses. Klaeson et al.11 considered that social norms were barriers for health professionals to feel comfortable about the subject and act professionally, and that nurses’ professional attitudes and knowledge were determining factors in approaching sexual health with men. Courtenay5 states that social behaviours that negatively impact men’s health frequently reflect societal notions of masculinity and serve as tools for men to navigate social power and status. Elements like ethnicity, income level, education, sexual orientation, and social environment shape the masculinity that men create, leading to different health risks among them.

In our study, Portuguese nurses considered that the only training opportunities in continuing education were occasional training courses run by pharmaceutical companies that produce drugs for sexual dysfunctions and whose application in practice was not considered significant. Participants emphasised the need to seek knowledge individually to be able to address issues about sexual health with men that include men’s cultural, gender and socio-economic specificities.

Klaeson et al.11 found that nurses felt more confident discussing sexual health with middle-aged men, especially those with conditions like diabetes that affect sexual function. This confidence was linked to prior training focused on addressing sexual health in the context of chronic illness.

Specialist nurses who participated in the FGs, considered that men and nurses are not at ease and prepared to address sexual health as a subject. According to them, this kind of subject is considered taboo, and men prioritise security, comfort, and accessibility when considering whom to turn to in case of problems. Due to the intimate character of sexual health, security is highly valued by men and considered a condition to be at ease discussing the subject. Nurses also recognise that men appreciate the anonymity achieved through digital technologies.

Digital technologies used in sexual health contexts pose challenges for nurses and health professionals, including the privacy and confidentiality of intimate data. The WHO30 published a technical sheet that provides a comprehensive overview of the landscape of artificial intelligence in sexual and reproductive health and rights, aiming to ensure that all individuals have access to and receive quality services and information. The WHO30 outlines the associated risks, implications, and policy considerations. Given the fast-paced advancements in artificial intelligence (AI), this brief aims to clarify its applications in sexual and reproductive health and identify critical issues to promote the effective, inclusive, and responsible use of AI. This document is aimed at implementers, policymakers, technology developers, funding agencies, implementing partners, and researchers involved in the intersection of AI and sexual and reproductive health and rights. Its goal is to foster a shared understanding among these diverse stakeholders.

Barriers to technology and connectivity remain a significant challenge, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Reports reveal disparities in mobile ownership and internet usage, highlighting that women in rural areas face the most limited access.

Class 4—issues surrounding men’s sexual health

Sexual health encompasses a multiplicity of issues that cross several areas of knowledge. Some of the participants represent sexuality globally as a life concern and emphasise the relevance of health professionals’ interventions to identify the impact of some therapeutics, and mental and chronic diseases, on them.

In our study, nurses highlighted three issues regarding men’s sexual health approach: reproductive issues, prevention and diagnosis of sexually transmitted infections (HIV in particular because of the threat it poses to couples’ lives), and sexuality in palliative care.

Our participants mentioned unsuccessful attempts to improve men’s access to sexual healthcare through the opportunistic approach to men during prenatal and postnatal appointments. They wonder if the fact of these appointments being sought out by women can be considered a barrier to men’s access. Specialist nurses who work in prenatal care shared examples of sexual and reproductive healthcare addressed to men and that are considered by peers to be good practices, one healthcare project that aimed to include men as women and children’s caregivers during pregnancy and postpartum, and one prenatal class only for men during prenatal care that is organized in one primary health care institution in Lisbon.

As factors that can be considered as barriers to a more comprehensive approach to sexuality, they mentioned age as a taboo – older people are seen by health professionals as asexualized and that includes older men; multicultural and communication barriers for nurses to addressing sexual health; nurses’ lack of preparation to deal with sexual diversity; and lack of visibility of sexuality and nursing interventions related to it, in most software’s used for electronic clinical records. Due to the private nature of sexual health, the fear of a lack of confidentiality was mentioned as a heavy barrier for men to access public sexual health services, especially for homosexuals.

From another perspective, specialist nurses whose professional practice was mainly in palliative care emphasised the need to help couples at the end of their lives to live out their sexuality and the relevance that they give to this kind of help. Despite the taboos surrounding sexual issues in healthcare, Benoot et al.1 stated that in palliative care, patients and their partners might experience dramatic changes in their sexuality and expect to have support from nurses to deal with it1,13. These authors consider that scientific evidence points out that the approach to sexual issues with patients/partners is still challenging for nurses. According to Saunamäki and Engström22, on the one hand, nurses feel obligated to do so, but on the other hand, they experience fear and embarrassment. Higgins et al.10 stressed that a lack of knowledge and skills contributes to nurses’ feelings of insecurity when addressing sexual issues, leading them to avoid these kinds of issues. Klaeson et al.11 mentioned that nurses in primary care expressed a need for additional education and knowledge about sexual health, and that healthcare organisations should be reformed to focus on this subject.

For nurses to be effectively prepared for the complexities of sexual healthcare, training must evolve beyond clinical proficiency to also cultivate advocacy and cross-sector collaboration. Ensuring equitable access to sexual health care requires nursing education to fully integrate critical topics such as the social determinants of health, health equity, and culturally competent care.

Also, adopting an intersectional approach—one that considers factors such as race, socioeconomic status, and sexual orientation—is essential for equipping nurses to recognize and address the unique barriers faced by diverse populations.

The World Health Organisation27 stated that improving sexuality-related counselling entails political and institutional investment in nurses’ and other health professionals’ training that clarifies and positively influences service providers’ values, with demanding follow-up supervision and support.

Class 5—settings for addressing men’s sexual health

From the participants’ perspectives, the symbolic charge of the spaces for men to access sexual health care and nursing care was also highlighted. In the national context, schools are highlighted as privileged settings for nurses to address the sexual health of boys and girls. In this approach, the so-called “question box” is underlined as an interesting and facilitating resource for responding to adolescents’ information needs.

However, there is no consensus on the nurses’ perspectives of schools as places to address sexual health. Some nurses find the approach taken in schools superficial. In contrast, others find it interesting because it is an everyday space for adolescents, outside of healthcare institutions, which seems to make it easier to discuss. In this context, and despite not describing joint actions with teachers, nurses recognise the contribution of teachers in the sexual education of adolescents. Another aspect that was only mentioned by specialist nurses concerned cultural and religious issues (as Muslim and Evangelical religions), which are represented as barriers to addressing some aspects of sexual and reproductive health.

Regarding the institutional settings in primary healthcare contexts such as sexual healthcare, nurses mentioned that often the barriers start right at the entrance, with questions from female managers. Our study, as the research conducted by Persson et al.21, illustrates how the discourses in the waiting room portray men and masculinity as mismatched.

Persson et al.21 stated that “In relation to the organizational discourse, men were depicted as unaware of their sexual health needs, and HCPs were doing men a favor by helping them. Participants described coaxing men to give them the necessary information. They described men as being blunt, unaccustomed to the situation, and untrained in terms of talking about sexual health and sexuality.” (p.9).

In Portugal, sexual and reproductive health settings exclude single men and are directed to a heterosexual population. According to our participants, men are only included as part of a couple, and nurses have clear reproductive goals to fulfil. They stated that some years ago, the designation of this kind of service was ‘family planning,” and that the fact that has been replaced by “women’s health” translates more unequivocally as men’s exclusion from this setting.

A positive approach to sexuality is not restricted to sexually transmitted infections but also covers them. As far as these are concerned, in Portugal, we have seen a significant increase in STIs (such as gonorrhea, lymphogranuloma venereum, and syphilis) and a larger number of men infected than women. WHO29 states that increasing evidence suggests that men are increasingly concerned about their health and wish to utilise health services. However, health systems organisations and the services offered often limit men’s access to HIV and related services. Specifically in sexual health, it is fundamental that health systems consider inclusive settings and strategies targeted at men and address male-specific barriers to care by providing person-centred services specific to men’s needs9.

Although Portugal’s healthcare landscape demonstrates strengths, such as its aim for universal coverage and encouragement of continuous professional development, current policies appear weak in addressing social factors that influence health, particularly for vulnerable groups, resulting in persistent disparities in access and health outcomes.

WHO29 highlighted that overarching strategies to address men are centered on three pillars: easy access to care (routine entry points, community-centered services, and flexible facility-based services), quality services (positive interactions with health care workers and integrated services) and supportive services (comprehensive counselling and facility navigation, peer services, and virtual interventions).

Misinformation and targeted disinformation must be contemplated when considering the Web as a setting to address sexual health. A key obstacle in employing AI for promoting men’s sexual health is the risk of misinformation, as AI models are trained on extensive datasets from the internet and social media, which often contain low-quality data and various biases30.

The responsible use of AI raises a set of ethical, legal, and human rights implications related to data governance, transparency, explainability, inclusiveness, equity, responsibility, and accountability29. Although these challenges exist in all healthcare sectors, the norms and power dynamics that influence decision-making in sexual and reproductive health highlight these concerns even more intensely.

Study limitations

This study faces several methodological constraints, primarily related to participant recruitment. Although efforts were made to ensure participant diversity, the use of referral-based recruitment may have introduced bias, as individuals often refer to others with similar backgrounds or viewpoints. As a result, the range of viewpoints represented here might be narrower than intended.

The decision to conduct focus groups online provided logistical convenience and broader accessibility. However, it also introduced challenges, especially with group interaction, keeping participants engaged, and noticing non-verbal communication. Even though participants seemed involved and shared their views openly, the online setting made it more challenging to pick up on subtle body language and other cues that are typically important in qualitative research, even when cameras were switched on.

Although IRAMUTEQ provides useful statistical tools for text analysis, like dendrograms, the results are not straightforward to interpret. Turning these statistical patterns into meaningful qualitative insights requires careful consideration and a more nuanced interpretation. To address this, the research team worked carefully to avoid oversimplifying complex ideas and ensured that the analysis remained rigorous throughout the process.

link