Persistent challenges remain in access to care

One-in-five say they don’t have a family doctor; two-in-five with one say it’s hard to get an appointment

Pour la version française, cliquez ici.

November 28, 2025 – The post-pandemic crisis of Canada’s health-care system continues as provinces struggle with recruiting family doctors and emergency room physicians. According to new data from the non-profit Angus Reid Institute, produced in partnership with the Canadian Cancer Society, one-in-five Canadians are without a family doctor, which is having ripple effects in accessing other parts of the health care system, including diagnostic and specialist appointments. Access to primary care is functioning as a gateway to better experiences in the health-care system, which could particularly impact screening for certain types of cancer, time to diagnosis and oncology appointments. Wider adoption of virtual care may be an avenue for better access to care, as three-quarters of Canadians are open to virtual care if it means faster diagnosis and treatment, and more than one-half are open to participating in clinical trials to help expedite their cancer care.

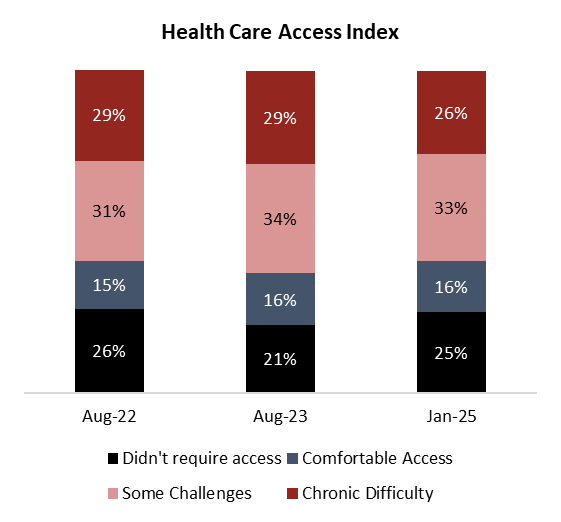

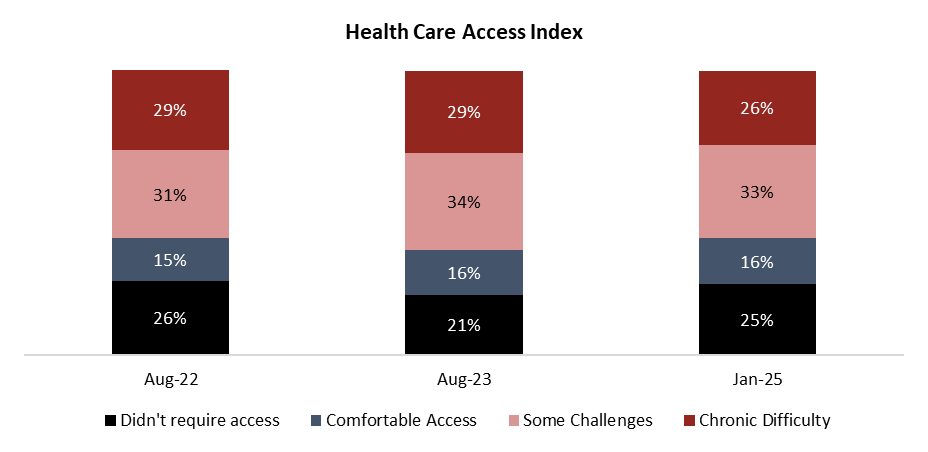

Overall, challenges in the health-care system that existed three years ago remain. One-quarter (26%) of Canadians report chronic difficulty accessing the health-care system, while one-third (33%) face some challenges. Both groups are significantly larger than the one-in-six (16%) who report comfortable access to the health care they say they needed in the past six months.

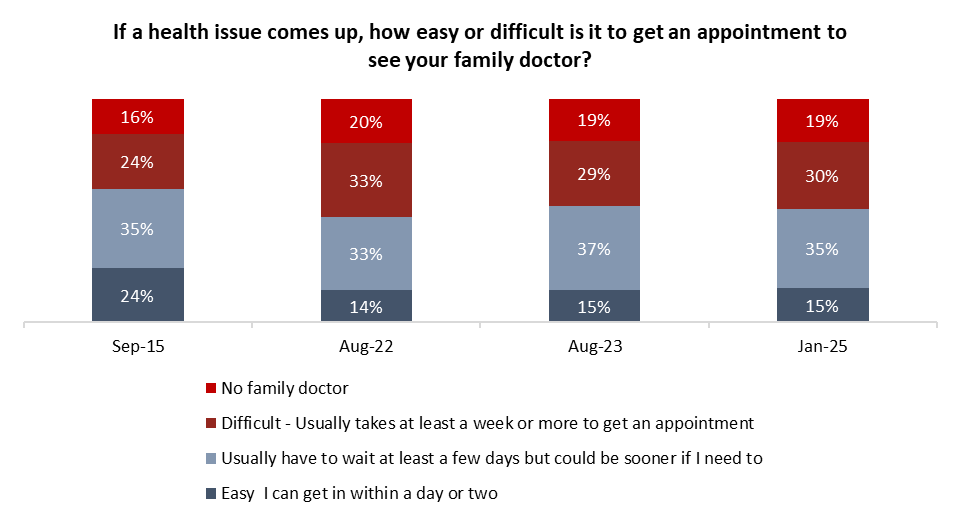

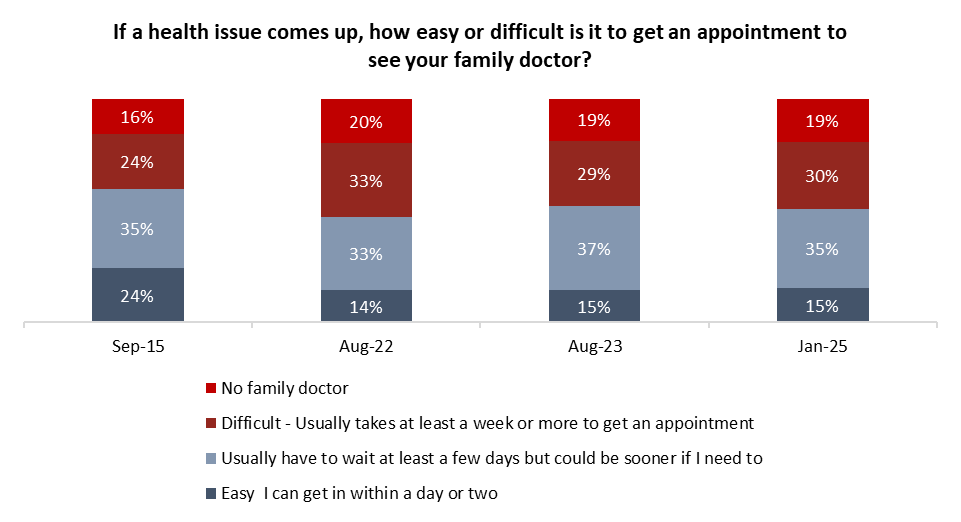

There is also a continuing gap in the estimated number of family doctors Canada needs, and the number of family doctors actually working in the system. This issue compounds itself when family doctors are tasked with too many patients for their practice. One-in-five (19%) say they don’t have a family doctor; a further 30 per cent of Canadians say they do have a family doctor but it’s difficult to get an appointment to see them.

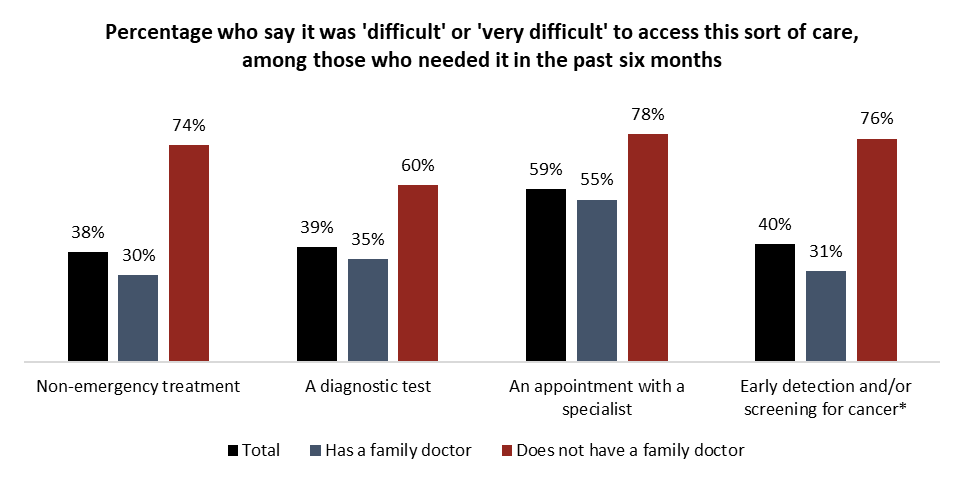

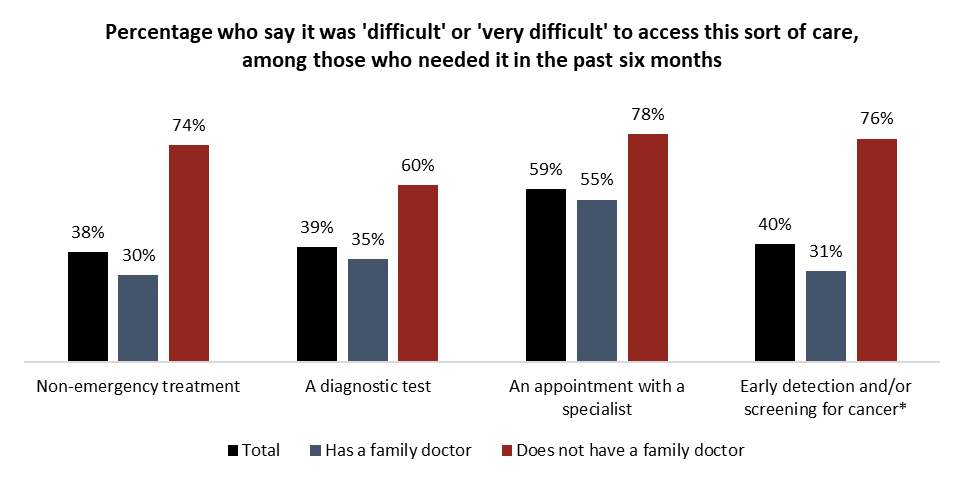

The importance of primary care providers is evident when comparing the health-care experiences of Canadians with a family doctor to those without. The latter group is much more likely to report difficulty accessing diagnostic and specialist appointments and non-emergency treatment than those who have a family physician.

The lack of family doctors also affects other key elements of the health-care system, including cancer treatment and diagnosis. Those without a family doctor are more likely to express challenges navigating that part of the system.

*Smaller sample size for those who do not have a family doctor, interpret with caution

More Key Findings:

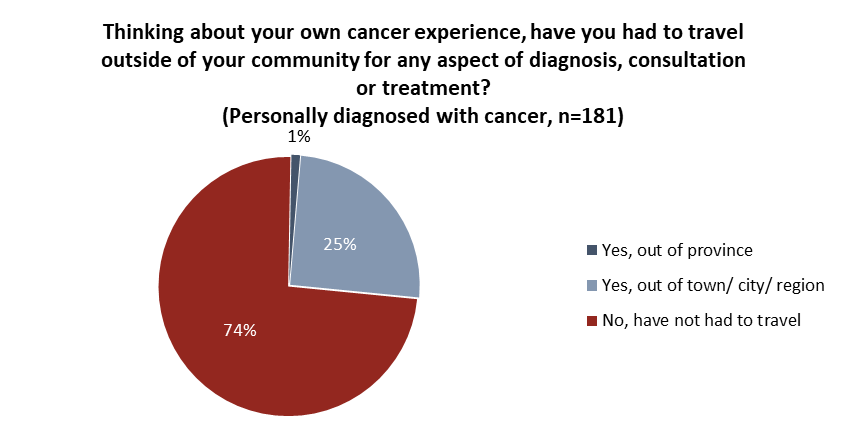

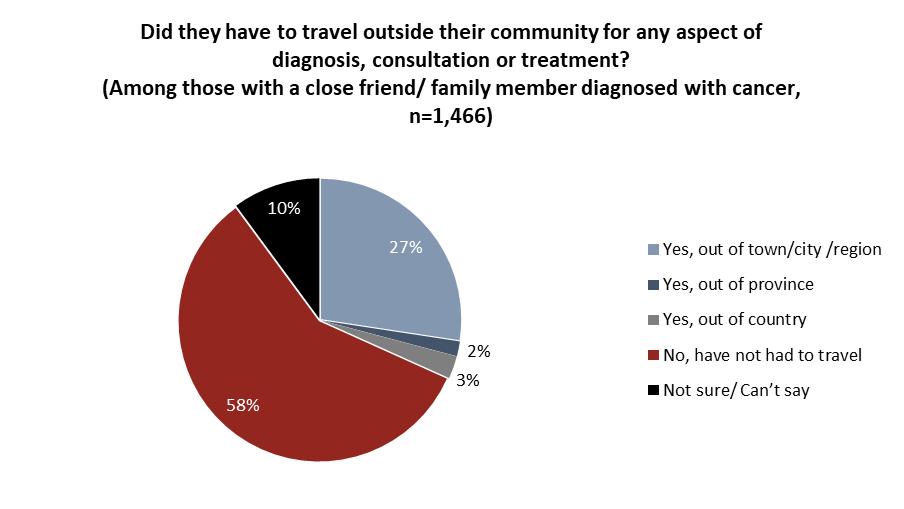

- Of those surveyed, nine per cent were personally diagnosed with cancer. Of these, one-quarter (26%) of people with cancer say they required to leave their community to get treatment. Canadians who say they had a friend or family member who needed out-of-community cancer care say it impacted their friend or family members’ mental health (71%) and finances (62%).

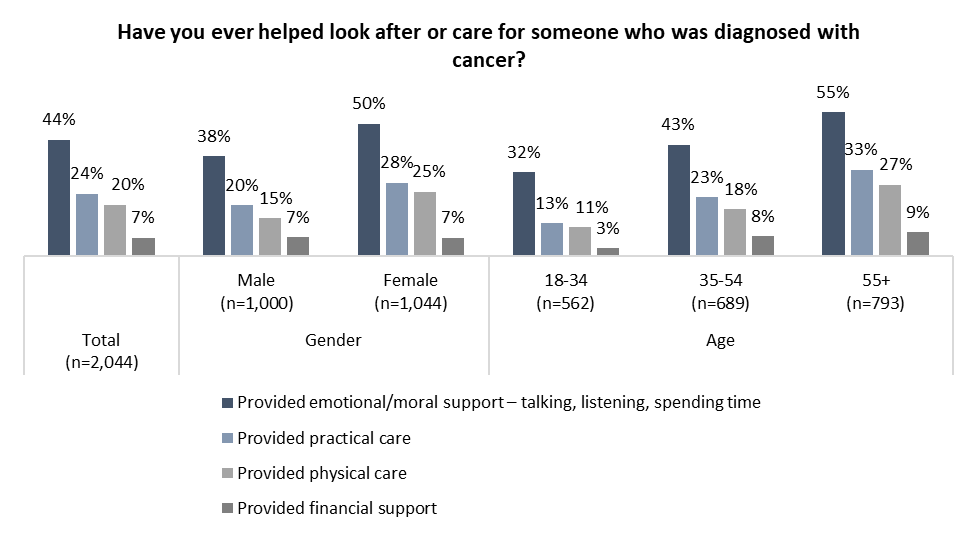

- More than two-in-five (44%) Canadians say they have provided moral or emotional support for someone dealing with a cancer diagnosis, while one-quarter (24%) have provided practical care and one-in-five (20%) physical care. Women, and particularly those older than 54, are more likely than men to say they have fulfilled those roles.

INDEX

Part One: Access to health care

-

One-in-five don’t have a family doctor; many who do struggle to get an appointment

-

Family doctors, a gateway to the health-care system?

-

Challenges persist for Canadians’ access to diagnostics, emergency care

-

The Health Care Access Index

Part Two: Assessments of cancer care

-

Out-of-town travel needed for one-quarter of cancer patients

-

Half say province’s cancer care is ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’

-

Most Canadians open to virtual cancer care if it means faster access, but hesitate on AI

Part Three: The importance of caregivers for cancer patients

-

Who has been a cancer caregiver?

-

Canadian cancer survivors tout value of caregivers

Part One: Access to health care

This report is the final in a multi-report series produced by the Angus Reid Institute in partnership with the Canadian Cancer Society exploring Canadians’ experiences with and perceptions of cancer and health care. The first part of this series provided insight into Canadians’ experience and proximity to cancer. It also provided background on how the out-of-pocket costs to accessing cancer care is a common barrier for people accessing health care in Canada. Almost two-in-five Canadians are expected to be diagnosed with cancer in their lifetime. Part two assessed Canadians opinions of clinical trials, which often provide people with cancer with access to new and innovative treatment options. Read both the previous reports below:

This final report will examine the persistent issues that remain among access to health care in Canada and its intersection with Canadians’ experience navigating cancer care.

One-in-five don’t have a family doctor; many who do struggle to get an appointment

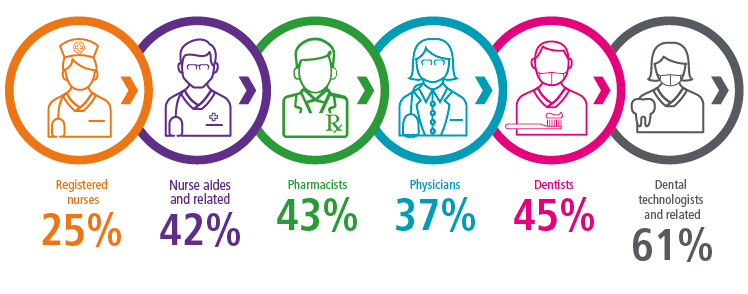

The struggle to address the family doctor shortage across the country continues. Health Canada estimated this year that Canada is short nearly 23,000 family physicians. Provinces are exploring different ways to address this, including changing payment models for family physicians and empowering other health care professionals to serve as primary care providers.

One-in-five Canadians tell the Angus Reid Institute and Canadian Cancer Society they don’t have a family doctor. This is a similar figure to that seen in August 2022, suggesting there has been little to no progress in addressing this key gap in the health-care system.

The family doctors in the health-care system are also overworked, with many taking on too many patients as a short-term measure to address this more systemic issue. This is reflected among the approaching two-in-five (37%) who have a family doctor who say that it’s “difficult” to get to see them (see detailed tables).

Taken together with those who do not have a family doctor, half (49%) of Canadians face barriers to primary care, either by not having a family doctor in the first place (19%) or struggling to get appointments with the one they have (30%):

Family doctors, a gateway to the health-care system?

The importance of having a family doctor is perhaps revealed when comparing the health care experiences of those without one to those that have one. Those without a family physician are more likely to report it was difficult or very difficult to access non-emergency treatment (74%), diagnostic tests (60%), and specialist appointments (78%) than those with one (30%, 35%, 55%, respectively).

There are also significant difficulties reported among the sample of Canadians in this survey who needed screening for cancer in the past six months but did not have a family doctor as a gateway to the system:

*Smaller sample size for those who do not have a family doctor, interpret with caution

Challenges persist for Canadians’ access to diagnostics, emergency care

While family doctors are an important key to the system, there are other challenges pressing Canadian health care. More than one-third (36%) of Canadians who needed a diagnostic test in the past six months say it was difficult or very difficult to access one. This has been the case for three years, according to ARI data:

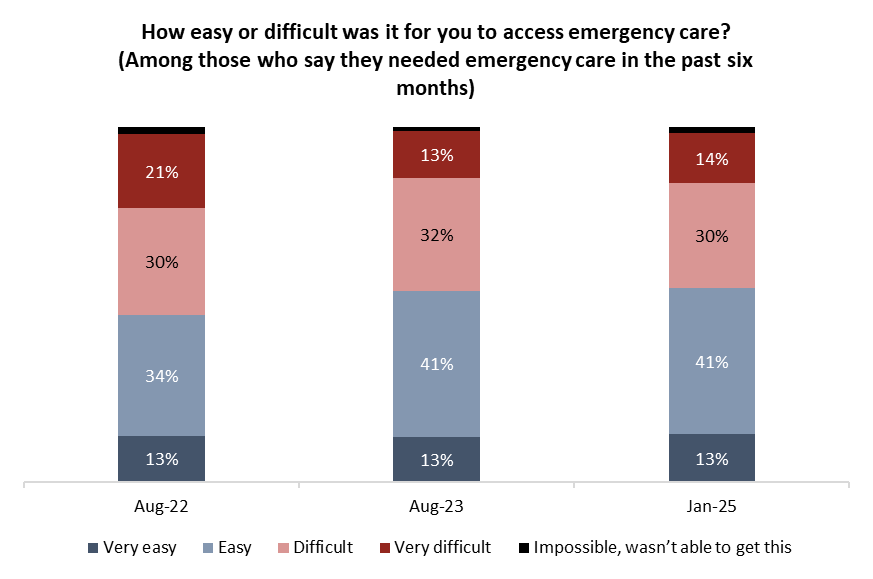

Emergency department closures continue to make headlines across the country. According to Globe and Mail data since 2019, there have been cases of 100-plus hours of emergency room closures or disruptions in every province in the country.

Among Canadians who needed emergency care in the past six months, more than two-in-five (44%) say it was difficult or very difficult to access it. While this is lower than the half (51%) who said so in 2022, it is evident that challenges in Canada’s ERs are a persistent issue.

The Health Care Access Index

To assess the trials and tribulations of Canada’s health-care system, in 2022, the Angus Reid Institute developed the Health Care Access Index. This amalgamated respondents’ answers to various questions about health care access, including whether they had a family doctor and whether it was easy or hard to access the care they needed from the system.

Related:

One-quarter of Canadians didn’t require access to the health-care system in the past six months. One-in-six (16%) reported Comfortable Access, while one-third (33%) had Some Challenges and one-quarter (26%) faced Chronic Difficulty in getting the care they say they needed.

Comparing the Health Care Access Index over time reveals that there continue to be significant issues Canadians are encountering in their health-care system.

Part Two: Assessments of cancer care

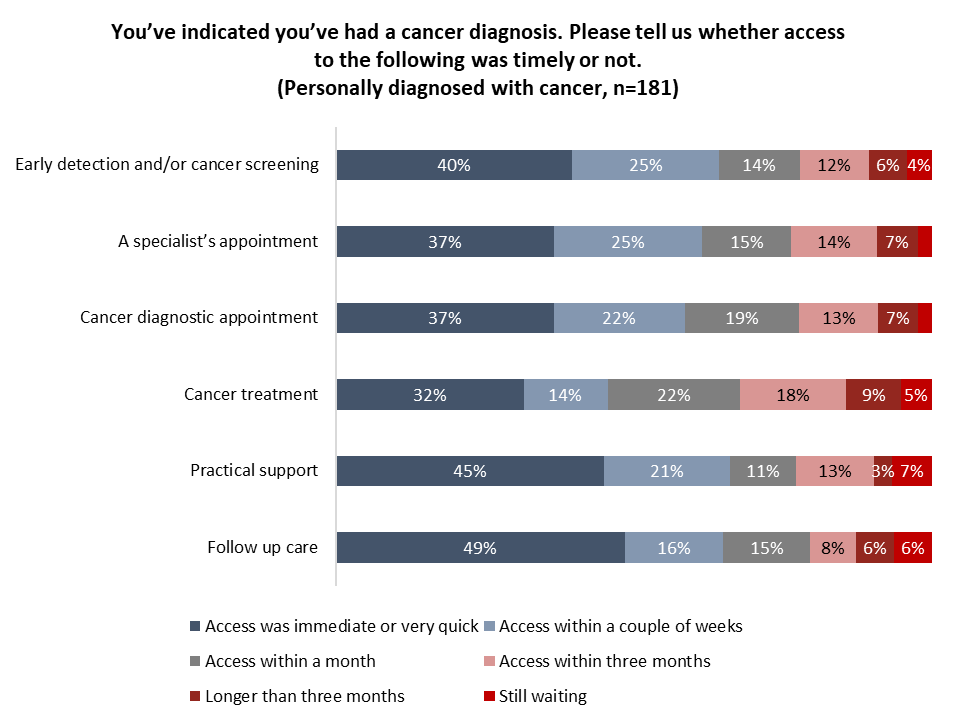

Canadians who have been diagnosed with cancer were asked to assess the timeliness of their access to cancer care. Speed of access can represent life or death for many diagnosed with the disease. A 2020 study review published by researchers from Queen’s University found that delayed treatment even by a month increases the mortality rate for cancer patients.

Among those personally diagnosed with cancer in this survey, access under one month to cancer screening (79%), specialist’s appointments (77%), diagnostic appointments (78%), treatment (68%), practical support (77%) and follow-up care (80%). However, there are warning signs that some patients are facing delays at key steps of their cancer experience, perhaps the most concerning being the one-third (32%) of Canadian cancer patients who say they waited more than a month for access to treatment for their cancer.

Data for cancer treatment are consistent with statistics from the Canadian Institute for Health Information, Canada’s leading body that collects, analyses and reports on wait times across Canada where data is available, which shows that the median wait time for cancer surgeries is between 22 and 50 days, while 90 per cent received treatment within two months. Most (94%) receive radiation therapy within one month.

Out-of-town travel needed for one-quarter of cancer patients

Canada, as a geographically disperse country, wrestles with issues with the distribution of its health care in general. Indeed, those living in rural areas of the country are less likely to have comfortable access to health care (11%) than those living in urban areas (17%) according to the Health Care Access Index (see detailed tables).

These access challenges are well documented in the area of cancer care as well. Cancer treatment centres are much more likely to be located in Canada’s largest urban centres, although approximately 16 per cent of the population of Canada lives in rural and remote areas.

Among Canadians who have experienced a cancer diagnosis, one-quarter (26%) say they were required to travel for some aspect of their treatment:

Out-of-community travel is a more common experienced reported by those who know close friends or family members diagnosed with cancer. Half (50%) of those living in rural areas who know someone close diagnosed with cancer also say that person had to travel outside of their community to get treatment (see detailed tables).

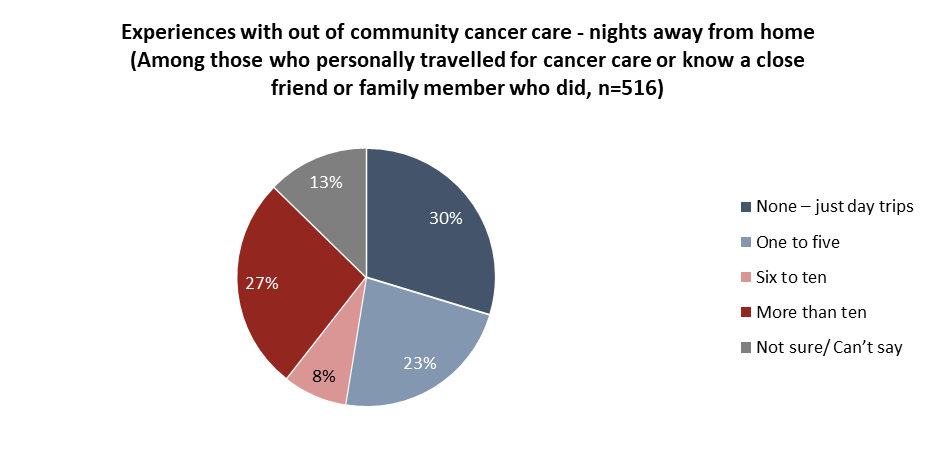

For many, their out-of-community cancer care experience was an extended one. Among those who either travelled outside of their community for cancer care for their own treatment, or those who know a relative or close friend who did, one-third say it was for six nights or more. Three-in-ten (30%) report that travelling outside of their home community for cancer care required only day trips:

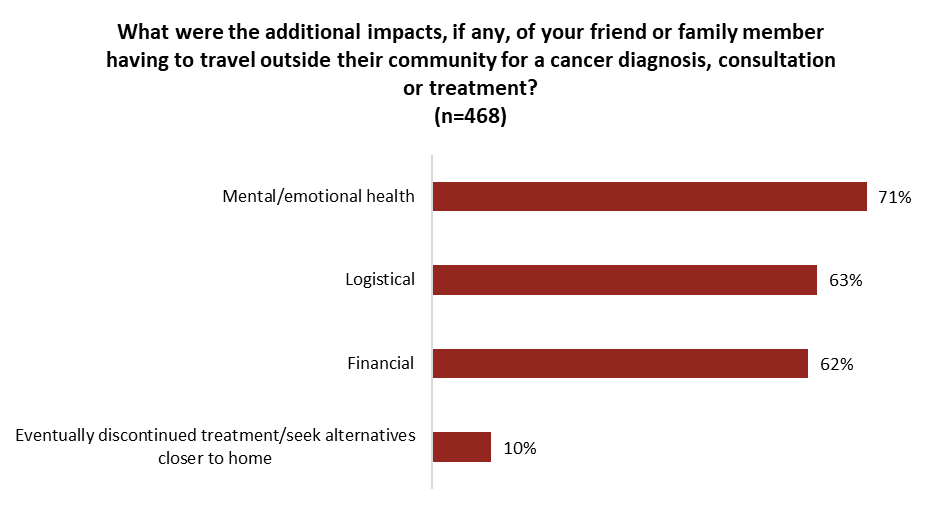

Seven-in-ten (71%) of those who knew a friend or family member who had to travel for cancer care say their friend or family member suffered consequences to their mental health, while similar sized groups of three-in-five said there were logistical (63%) and financial (62%) impacts. One-in-ten (10%) reported that their friend or family member discontinued treatment to seek alternatives closer to home:

Half say province’s cancer care is ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’

Canadians’ evaluations of health care within their own province are generally negative. A majority in all provinces believe their provincial government is performing poorly on health care, according to data from June from the Angus Reid Institute.

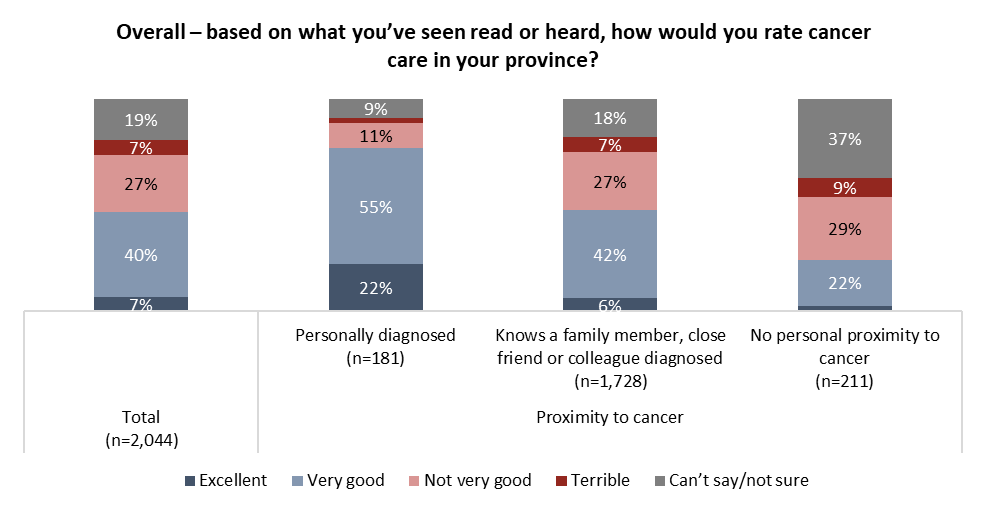

Despite this, Canadians are more positive than not about their province’s cancer care. Approaching half (47%) rate it as at least “very good”, while one-third (34%) believe it to be worse than that. Among those who have been diagnosed with cancer, more than three-quarters (77%) say cancer care in their province is good.

It is important to note that there may be survivorship bias in these data because this sample of Canadians with personal experience with cancer would not include those who have died or those who are too ill to participate in a survey.

A more negative experience with the system is perhaps captured from Canadians who know a friend or family member who has been diagnosed. That group is much more likely to say cancer care in their province is not very good (27%) or terrible (7%). There is an important caveat with these data: those without personal experience may be recalling the experiences of multiple people and reporting on the worst of those.

Most Canadians open to virtual cancer care if it means faster access, but hesitate on AI

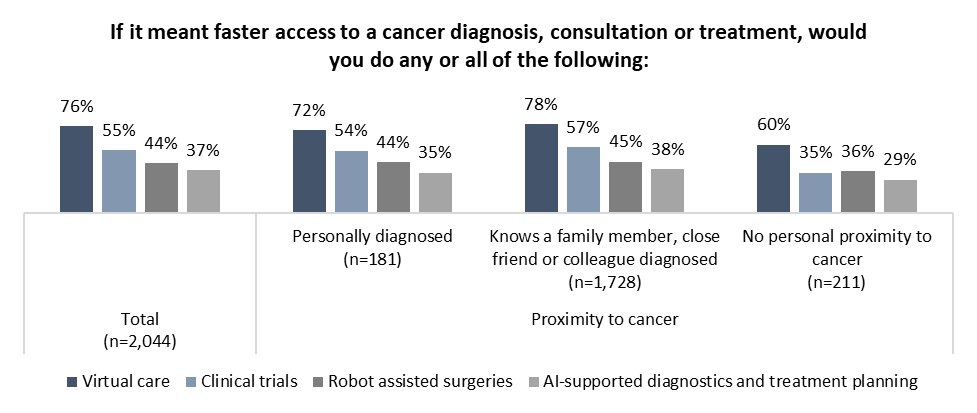

The future of cancer care may involve increasing the use of technology. The COVID-19 pandemic perhaps opened the door to wider adoption of virtual health care, including some elements of cancer care. Three-quarters (76%) of Canadians say they are open to virtual care if it means faster access to cancer diagnosis and treatment. A majority (55%) also express openness to participating in clinical trials to accelerate their cancer care.

Related: Cancer in Canada: Nearly all Canadians support federal government increasing access to clinical trials

There is more hesitation from Canadians when it comes to other potential technological advancements. Fewer than two-in-five (37%) say they would participate in AI-supported diagnostics and treatment planning even if it meant faster diagnosis and treatment:

Part Three: The importance of caregivers

Who has been a caregiver?

People’s experiences with cancer can be challenging, and support from others plays a crucial role. Canadians rely on their friends and family for support as they deal with the ups and downs of diagnosis and treatment. More than two-in-five (44%) Canadians say they’ve provided emotional support for someone with a cancer diagnosis, while one-quarter (24%) have provided practical care, one-in-five (20%) physical care and one-in-12 (7%) financial support.

Older Canadians, who are much more likely to know someone who has been diagnosed with cancer, are more likely than younger ones to have filled all four roles. There is also a significant gender gap when it comes to men and women who have provided moral support (38% of men, 50% of women), and practical (20% vs. 28%), and physical (15% vs. 25%) care of someone who has been diagnosed with cancer:

Canadian cancer survivors tout value of caregivers

A report by the Canadian Association of Provincial Cancer Agencies (CAPCA) noted that families and caregivers are “play[ing] a more active role in care delivery”, which can “improve quality of care”.

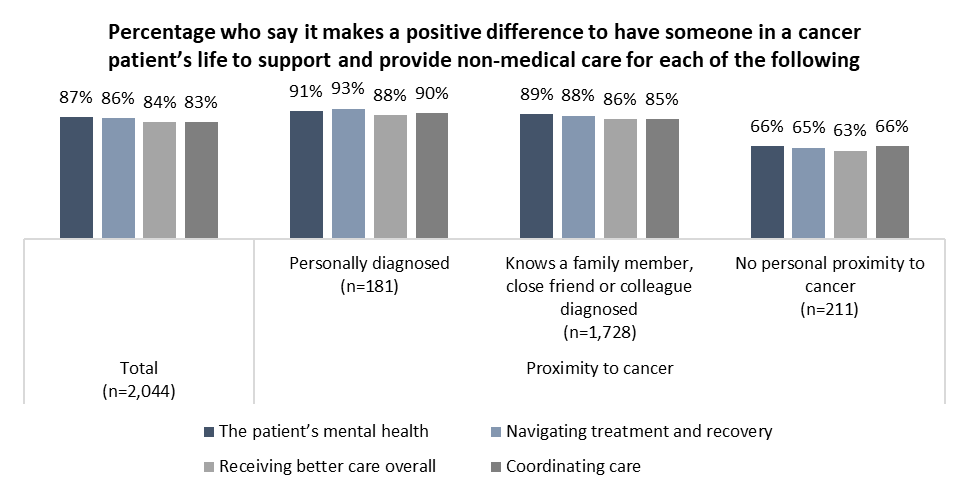

Canadians who have been diagnosed with cancer are more likely than others to recognize the positive value brought by having someone in their corner. Nearly all say having someone provide support to a cancer patient is positive for the patient’s mental health (91%), navigation of treatment (93%), coordination of care (90%) and care overall (88%). Though a majority of those with no personal proximity to cancer say the same, they are more likely to express uncertainty about the value of caregivers.

It appears that the value of caregivers is truly recognized by those who are going through care, and perhaps caregivers deserve more consideration in health care planning.

Survey Methodology

The Angus Reid Institute and the Canadian Cancer Society conducted an online survey from Jan. 10-17, 2025, among a randomized sample of 2,044 Canadian adults who are members of Angus Reid Forum. The sample was weighted to be representative of adults nationwide according to region, gender, age, household income, and education, based on the Canadian census. For comparison purposes only, a probability sample of this size would carry a margin of error of +/- 1.5 percentage points, 19 times out of 20. Discrepancies in or between totals are due to rounding. The survey was self-commissioned and paid for by ARI and CCS.

How we poll

For detailed results by age, gender, region, education, and other demographics, click here.

For detailed results by proximity to cancer and the Health Care Access Index, click here.

For full release including methodology, click here.

For questionnaire, click here.

Pour la version française, cliquez ici.

About ARI

The Angus Reid Institute (ARI) was founded in October 2014 by pollster and sociologist, Dr. Angus Reid. ARI is a national, not-for-profit, non-partisan public opinion research foundation established to advance education by commissioning, conducting and disseminating to the public accessible and impartial statistical data, research and policy analysis on economics, political science, philanthropy, public administration, domestic and international affairs and other socio-economic issues of importance to Canada and its world.

About the Canadian Cancer Society

The Canadian Cancer Society works tirelessly to save and improve lives. We raise funds to fuel the brightest minds in cancer research. We provide a compassionate support system for all those affected by cancer, across Canada and for all types of cancer. Together with patients, supporters, donors and volunteers, we work to create a healthier future for everyone. Because to take on cancer, it takes all of us. It takes a society.

Help us make a difference. Call 1-888-939-3333 or visit cancer.ca today.

MEDIA CONTACT:

Shachi Kurl, President, ARI: 604.908.1693 [email protected] @shachikurl

Victoria Young, Communications Coordinator, CCS: 416-572-4252, [email protected]

link