Should healthcare professionals include aspects of environmental sustainability in clinical decision-making? A systematic review of reasons | BMC Medical Ethics

Overview of the sample

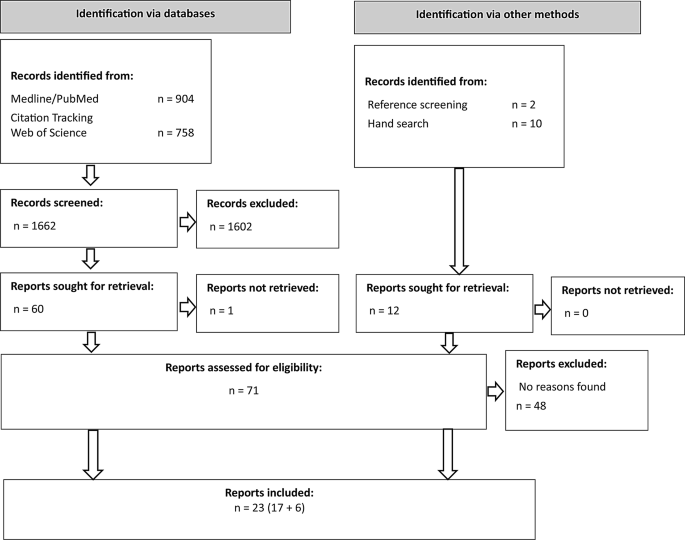

The search in PubMed yielded 904 publications. Citation tracking of PubMed full texts in Web of Science identified a further 758 publications. Consequently, 1,662 publications were screened by title and abstract. After this first screening stage, 1,602 publications were excluded, one publication could not be retrieved. A total of 59 full-text publications were screened, of which 17 met the inclusion criteria. In addition, 12 publications were identified via hand search and reference screening of included publications. After screening the title and abstract, six of these publications were excluded in the full-text screening. Finally, 23 publications were included in the analysis (see Fig. 1).

Flow diagram for study selection

An overview of the metadata of the 23 publications included can be found in Table 2, additional information can be found in Supplement 2. Notably, all first authors are affiliated with institutions in high-income countries. Table 2 shows the topics of the publications as clustered by SGK. There is a clear dominance of the debate on inhalers mentioned above, which concerns the use of more climate-friendly DPIs instead of MDIs for chronic lung diseases. Furthermore, there is a debate on professionalism concerned with the attitudes of healthcare professionals towards addressing ecological sustainability, particularly regarding the arguments of professional associations and guidelines on the subject. The reproductive medicine debate focuses on the arguments of antinatalism, as a topic of contemporary ethics that is gaining importance in light of the climate crisis. Its main argument is against procreation, as an increase in the global population results in elevated GHG emissions, thereby intensifying the climate crisis [28].

A total of 67 ethical reasons for, against or ambivalent regarding the research question were identified. Thirty reasons were identified in favor of integrating aspects of environmental sustainability into clinical decision-making. Conversely, 27 reasons were identified against implementing such measures, while 10 reasons were assessed as ambivalent as the authors’ tendency of using these reasons could not be clearly determined. A comprehensive table of reasons (Supplement material 3) and the code tree (Supplement material 4) can be found in the supplementary material.

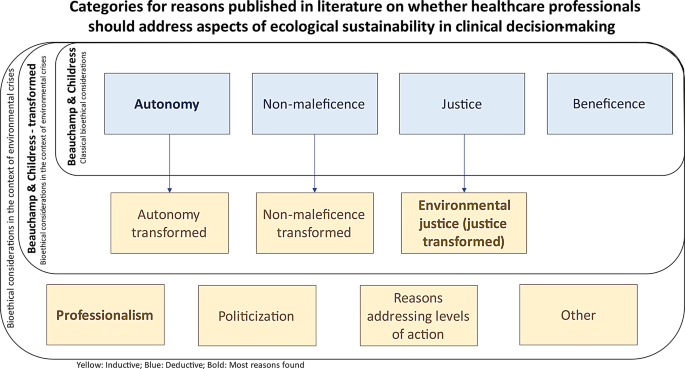

Illustration of deductive and inductive categories

Reasons related to respect for patient autonomy

We found most reasons in the deductive category of respect for patient autonomy (see Fig. 2; Table 3), with most of those reasons being against implementing aspects of environmental sustainability in clinical decision-making. These reasons focused on the classic individualistic definition of patient autonomy, centered on one single patient, as advocated, for example, by Beauchamp and Childress. Concerns were expressed regarding the potential loss of trust on the part of patients in the physician providing care when an inhaler is switched without the patient’s consent, or an offered switch is turned down by the patient, but this wish is not respected by the physician [29]. One ambivalent reason stated that “(…) [W]hat is morally right or wrong for patients to choose is normally not seen as relevant for the issue of whether or not their autonomy should be respected” [30].

The category of shared decision-making as a subcategory of respect for patient autonomy yielded a considerable number of ambivalent reasons and reasons against. The reasons against focused on not “impos[ing] environmental protection values on [a patient’s] decision-making” [31] from the physician’s side, while the ambivalent reasons looked at the setting in which those conversations would occur (e.g., focusing on sensitive and patient-centered communication) [29] or on the necessity of decisions being made collaboratively [32, 33] – instead of paternalistically. However, the positive reasons regarding patient autonomy were found multiple times in different text segments of different publications, highlighting the fact that “a healthcare provider might be withholding information if she did not provide the patient with environmental data” [34] and, thus, potentially leading to a breach of respect for patient autonomy.

Furthermore, two text segments indicated a certain transformation of the classical definition provided by Beauchamp and Childress. One author argues that “when self-interest and inadequate resources harm others, autonomy loses integrity,” [35] which broadens the scope of patient autonomy and provides a reason for the implementation of environmental sustainability in clinical decision-making. Respect for autonomy is, therefore, not understood as an absolute means, as patients’ decisions must meet certain moral criteria in order to be considered to have integrity. This creates a tension between the principles of autonomy and justice.

Reasons related to justice

The concern was expressed that addressing climate issues in the consultation could perpetuate injustices, as many people in the consultation belong to vulnerable groups already, especially in the debate around reproductive medicine and coerced sterilization [31]. Indeed, there are also some scholars now arguing that in light of the climate crisis, there is a duty to have fewer children, if any at all, referring to the concept of antinatalism [36,37,38]. Taking these reasons into account, it seems reasonable to conclude that there is a potential risk that those who have been victims of injustice in the past may be forced to forego certain medical treatments that are harmful to the climate. Again, the tension between autonomy and justice becomes apparent when a patient’s own decision-making power is potentially limited by considerations of GHG emissions of healthcare interventions.

By contrast, it was argued in a transformed understanding of justice (see Fig. 2; Table 3) that addressing environmental sustainability would align with the global public health responsibility and, thus, set the focus on the “global ethical priority” to reduce GHG emissions [34]. This would transcend the individual-oriented notion of justice, as defined by Beauchamp and Childress, and instead focus on a global idea of justice, and on public health rather than individual health. One might conclude that this could be at the expense of individual patient autonomy and instead benefit third parties, for example future generations or distant communities.

Reasons related to non-maleficence

In terms of non-maleficence, Wiesing argues that “(…) if the best intervention is not chosen for environmental reasons and the patient is not treated optimally and worse off, then there is a serious conflict” [39]. This would mean causing or risking harm by not treating patients optimally and violating the principle of non-maleficence.

However, a broadening of the focus was also found here, where some authors pointed out that future generations also have a right to not be harmed [40]. Parker, for example, introduces the duty to “minimise expected harm,” [14] which refers to potential environmental harm resulting from healthcare interventions that negatively affect third parties (e.g. future generations), and would be accompanied by an advocacy for addressing sustainability issues with patients.

Reasons related to beneficence

Beneficence was a rather small category, with only two, albeit positive, reasons found. It was stated in a case presentation on the debate on reproductive medicine that taking time as a doctor for a patient to “(…) consider […] the potential environmental impact of a subsequent pregnancy and whether it is acceptable to bring a new child into the world at this time is in accordance with the principle of beneficence” [31].

Reasons related to professionalism

The most comprehensive inductive category is that of healthcare professionalism (see Fig. 2; Table 3). While reasons regarding the understanding of physicians’ roles were frequently mentioned, other health professions were only addressed rarely. Reasons against the implementation of sustainability aspects included concerns that there would be an undue burden of responsibilities on health professionals and that the physician-patient relationship is ill-suited for the resolution of complex ethical issues that presumably cannot be resolved only at the individual level [39]. By contrast, arguments in favor of addressing climate protection include the assertion that this is simply part of the doctor’s professional remit, even now [41]. With a change in physicians’ practical identity, as has already happened in the past regarding patient autonomy as a principle, “(…) climate protection [can be] perceived (…) as part of the physician’s ‘job’ [and] raising such issues in the clinical encounter might come up more naturally and be less irritating to patients” [41].

Some reasons identified refer to the codes of medical associations. Some authors noted that a few physicians’ codes already emphasize the practice of medicine in an environmentally sustainable manner, such as the World Medical Association’s International Code of Medical Ethics [42] in its last revision of 2022 [41]. Conversely, other authors have noted that other codes of conduct explicitly prioritize the individual patient, as ten Have points out, citing the Declaration of Geneva in its 2006 version and UNESCO’s Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights, also in its 2006 version [43]. The most recent update of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Geneva [44] in 2017 also states that “the health and well-being of my patient will be my first consideration” [44], with a similar wording to the two above.

Reasons related to politicization

It has been noted in the debate on the politicization of medical consultations, that politicization in a physician’s office is not an uncommon phenomenon, with physicians discussing “abortion care, transgender care, sexual and reproductive health, lifestyle counselling and end-of-life counselling” [45]. Cohen et al. point out that physicians are experienced and equipped to deal with politicized issues such as the above; climate change would simply add to this list [45]. Furthermore, the discourse within the medical consultation can serve to inform the patient about the issue under discussion, which may subsequently “open opportunities for patients to consider other ways in which they can protect the environment.” [46].

General practitioners were “(…) reluctant to discuss reproductive health with patients (to limit unwanted pregnancies and population growth)” [47] only in one qualitative study with such doctors on communicating about the climate crisis with their patients. Here, the topic of reproduction was perceived as too politicized.

Reasons related to appropriate levels of action

Looking at appropriate levels of action that could be targeted for measures in climate protection, it was pointed out that addressing the meta level of healthcare in terms of a structural or institutional approach alone will not solve all the problems, as it cannot be “divorced from the interactions that doctors have with their patients” [48].

However, the claim still stands that healthcare providers “should focus on advocating for system-level changes in health care financing, organization, and delivery whilst using discretion when bringing up environmental concerns with their patients” [49]. Furthermore, Herlitz et al. argue that focusing solely on the individual and the micro level would “weaken […] the attractiveness of [the] move towards ‘green’ bioethics” [30].

Other reasons

Another reason against the inclusion of environmental sustainability aspects in the consultation is worth mentioning, but was only discussed once in the literature included: the difficulty of quantifying emissions, not only from the technical point of view of implementing the correct method of calculation [50, 51], but also in terms of the ethical implications, as this endeavor can be “value laden and morally complex to implement in practice” [52].

link