Reducing the environmental impact of nitrous oxide in dentistry: a national quality improvement project

This is the first study to quantify the real-life environmental impact of N2O in dentistry across different settings in the UK. It supports previous data that the use of inhalation sedation in dentistry contributes to the environmental burden.6 Any dental service using N2O should be aware of this impact and take steps to reduce it.

The carbon footprint in this QIP is based on the N2O gas administered to patients, and does not include the environmental footprint of wasted gas, materials, running the dental surgery, servicing equipment, or patient and staff travel. This QIP was conducted in 2023/24, when the global warming potential of N2O was 265.5 This has since been updated to 273, so the carbon footprint is likely a slight underestimation.

The high success rate of IS observed in this study aligns with existing literature,4 reinforcing the benefit of this form of sedation for dental patients, especially considering alternatives are not universally available in all services, and have more restricted eligibility criteria. A majority of the sedation episodes were for paediatric patients, where N2O sedation is the only standard sedation technique available.2,3 Given the benefit to patients, and lack of a like-for-like alternative, the authors support the continued use of N2O in dentistry at this time, where it is supplied and administered responsibly.

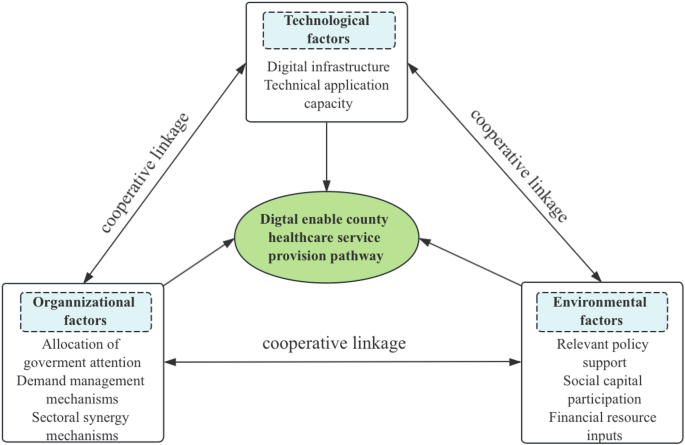

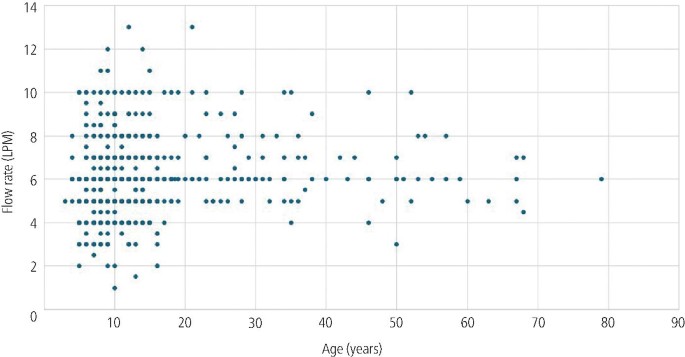

The study identifies significant variation in the clinical administration of N2O across the country, highlighting the relatively unregulated nature of this form of sedation and the need for standardised staff training on administration. As an example, flow rate varied greatly between services and had a greater impact on the overall carbon footprint than the N2O titration. A flow rate that is greater than clinically necessary does not hold any additional patient benefit but does increase the volume of N2O used, and therefore the carbon footprint and harm to the planet. Flow rate did not appear to relate to patient age, so it is likely that the variation reflects clinician training or preference. Another possibility is that the scavenging volume is too high, meaning that higher flow rates are needed to maintain the volume in the reservoir bag. Scavenging is recommended at 45 LPM in dental sedation guidelines,2,3 but there is no standard about how or when this should be tested. The 45 LPM figure is based on the average lung capacity of an adult, and therefore the authors of this study question whether it should be applied to every patient having dental sedation without further evidence.13 The authors advocate for further research into safe scavenging levels, and how to test scavenging levels in daily practice, as this may help to reduce the flow rates needed to inflate a reservoir bag. Alternatively, sedation machines that eliminate the need for a reservoir bag have the potential to reduce the gas volumes administered to patients.

A variety of dental procedures were provided under IS in this study, including acclimatisation procedures in some services. An additional visit to acclimatise the patient to IS results in more N2O used for that patient’s course of treatment, as well as more visits for that patient to attend. Although acclimatisation aims to increase the success rate of treatment, this study did not observe higher success rates for services using sedation for acclimatisation, compared to those that did not. Given the lack of difference in success, and the additional environmental cost, this study would not support acclimatisation under sedation as routine. The decision on whether to offer an acclimatisation visit under sedation should be considered on an individual patient basis.

Wastage refers to the proportion of N2O gas that is not used for patient care. Wastage estimations in this study were based on short data collection periods and relied on patient notes, and so this is considered an estimation rather than formal calculation of wastage. The method of wastage estimation differs from studies in anaesthetics, where the gas volume is measured by the anaesthetic machine, so comparison of the wastage figures in this study to other healthcare settings is not appropriate. Although the average wastage was greater in sites with a central piped supply, there was huge variation in wastage in both cylinder and piped supplies. There are no set standards on what an acceptable level of wastage is. The authors suggest that wastage is monitored in every service providing sedation, regardless of cylinder or manifold supply, and steps are taken to address any potential cause of wastage. During this study, services with ‘high’ wastage (greater than 25%) were asked to investigate stock control (for example, were unused cylinders left to expire or stolen, were cylinders changed too early), and faulty equipment (for example, piping leaks and faulty cylinder gauges). Based on the national average volume of N2O per episode of sedation, one size E cylinder should last for approximately 32 episodes of IS, if there is minimal wastage.

The main limitation of this QIP was the short data collection periods, meaning that data may not be representative of normal sedation activity throughout the year. Furthermore, the CO2e calculation relied on accurate recording of flow rate, time, and titrated dose. Flow rate and titrated dose can vary throughout the sedation procedure, and titrations are typically increased slowly at the start of the procedure. Ideally, the sedation machine would include a metre reading that identifies exactly how much gas has passed through it. This is a feature of anaesthetic machines and would make wastage estimations comparable to anaesthetics, more accurate, and more practical to routinely monitor.

This QIP was conducted on a voluntary basis with no incentive for participation. The QIP was advertised to BSPD members, and so participants may be over-representative of paediatric dentistry, and under-representative of special care dentistry and oral surgery services. Dental practices were also under-represented.

Table 1 outlines some simple recommendations to dental services that use N2O, alongside some potential actions or quality improvement activity to reduce the environmental impact of the N2O, while maintaining patient care. Recommendations would vary between sites depending on their service, how N2O is clinically administered and supplied, and how much is wasted. Ideally, a toolkit would be produced with a step-by-step guide on N2O reduction, which is currently in development by the authors.

In an ideal world, the clinical need for N2O in dentistry would be eliminated by a suitable alternative inhalation agent. Further research is needed into potential alternatives, such as methoxyflurane (Penthrox),14 and consideration of whether to include it in dental conscious sedation guidelines. Currently, Penthrox is licenced for adults only in the UK, and so would not apply to a majority of N2O sedation in dentistry, which is done on children and young people.15 Alternatively, the safety and practicality of providing alternative forms of sedation in dental settings (such as midazolam given orally, nasally, or intravenously) should be considered at each guideline update, so that access to these alternatives can be improved, and our reliance on N2O reduced.

Finally, industry will play a role in reducing N2O in dentistry. As flow rates had the biggest impact on the overall carbon footprint, any innovations that reduce or eliminate the flow rate would have the greatest impact on the carbon footprint. Ideally, all services would have a direct cylinder supply, with two cylinders attached to the mixer via an automated gauge that allows one cylinder to run fully empty, and then switches automatically to the back-up cylinder. Furthermore, it would be ideal if all sedation machines included a ‘metre reading’ of how much N2O has passed through the machine, as this would make wastage estimations simpler and in line with methodology used in anaesthesia.8,9

Capture-and-destruction technology has been touted as a way to mitigate the environmental impact of N2O in healthcare settings, such as maternity.16 It is important to note that although this technology has good evidence for the capture of N2O molecules (i.e., scavenging and the occupational health benefit), the authors are not yet aware of any real-world data on its effectiveness of destruction of the N2O molecules (i.e., the environmental benefit). Additional research is needed into this capture-and-destruction technology in dental settings, including the costs and benefits (both financial and environmental). In line with the latest guidance, until there is further evidence, the authors would recommend that dental services focus on wastage and clinical administration before considering this technology.10

link