Integrating an occupational therapist into a primary health care team: a mixed-method evaluation of a home-based service delivery | BMC Health Services Research

Qualitative methods study

Six themes summarized the lived experiences of the OT and the stakeholders in implementing an OT program in the PHC center:

(1) introduction of the OT role, (2) team coordination, (3) impact on team functioning, (4) impact on patients and caregivers, (5) contributions of the OT, and (6) structural limitations and challenges. Tables 1 and 2 present verbatim extracts corresponding to the categories within these six themes.

Introduction of the OT role (Theme 1)

The incorporation of an OT into the home-based care team fostered collaboration and alignment with the PHC services; however, early implementation was hindered by a barrier—an initial lack of role awareness (C1.1). Many PHC professionals from the pre-existing team and patients were unfamiliar with the OT as a global health professional, often limiting the scope of the role to poststroke rehabilitation. The OT had to repeatedly explain the role and its associated skills, often in simple terms, while the PHC nurses frequently served as intermediaries to introduce the new role.

The positive reception of the role (C1.2) was consistent once explained. Patients responded with openness and gratitude, and professionals, initially skeptical, came to appreciate the OT’s contribution in addressing unmet functional and social needs. This shift in perception was grounded in the observed outcomes and the OT’s ability to collaborate and communicate effectively, aligning with existing team workflows.

The introduction and integration process (C1.3) involved structured efforts to position the OT within the existing workflows. The OT conducted team presentations, clarified the referral criteria, and aligned with the PHC nursing staff to identify patients who might benefit. Combining internal advocacy with patient-centered communication enabled the team to understand, accept, and operationalize the OT role gradually.

Team coordination (Theme 2)

The OT was perceived as autonomous and consistently aligned with the PHC team’s goals. The OT interventions were primarily conducted independently in the field but remained tightly connected to broader team activities through structured collaboration and routine communication.

The balance between autonomous and integrated work was a defining feature (C2.1). The model of autonomy, based on an initial patient caseload, enabled the OT to provide specialized input without disrupting established teamwork, while maintaining high visibility and coordination. As the OT explained, “At the start of the day, I usually go over the agenda, organize tasks, and think about how to structure the workday… part of this time also involves telephone follow-up or patient contact.” PHC nurses and GPs perceived this as a practical and effective way to incorporate a new role within care environments. Emphasis on fluid and shared communication was equally important (C2.2). The OT was described as communicative and accessible, engaging in ongoing dialogue with the PHC nurses, the GP, and the social worker. In addition to planned regular exchanges, this fluid information exchange also occurred informally, ensuring consistency in care plans and responsiveness to patients’ evolving needs.

Impact on team functioning (Theme 3)

The integration of the OT into the home-based care team led to significant changes in internal dynamics, collaboration patterns, and task distribution; the OT’s presence often encouraged reflection, innovation, and cohesive teamwork.

New team dynamics (C3.1) emerged with the OT’s focus on functionality, environment, and caregiver support, which broadened the team’s perspective on patient care, fostered interdisciplinary dialogue, and promoted a holistic approach, including joint case discussions and shared care planning. The inclusion of OT was perceived as transformative, prompting the team to adopt more integrated and reflective approaches to their work. Simultaneously, task redistribution (C3.2) improved efficiency. Responsibilities previously handled by PHC nurses were gradually transferred to the OT. Both nurses and the OT described this shift as beneficial: nurses saw it as an opportunity to reduce their workload, while the OT considered it an efficient use of expertise. As one nurse explained, “I’m not an expert in fall prevention, so I feel much more at ease when I visit a patient who tells me, ‘I fall frequently.’ In that case, I know I can refer the patient to the OT, and I trust that the OT will take the appropriate actions.” Stakeholders widely acknowledged that this redistribution improved collaboration and enhanced the team’s overall functioning.

Nonetheless, GPs and PHC nurses experienced difficulties and adjustments (C3.3) during the integration of OTs. They expressed uncertainty regarding referral criteria, role overlap, and the integration of this into established workflows. These challenges were primarily addressed through open communication, mutual learning, and the observation of improvements in patient outcomes, as reported by the OT.

Impact on patients and caregivers (Theme 4)

The OT interventions were perceived to have a multidimensional effect on both patients and their informal caregivers. The OT addressed not only physical limitations but also the emotional and relational aspects of care, particularly for individuals with chronic conditions.

The central benefits reported were improved function and increased participation (C4.1). The OT tailored interventions to patients’ environments and goals, facilitating the recovery or maintenance of autonomy in daily tasks such as mobility, self-care, and household activities, which patients described as contributing to increased confidence and a sense of purpose. Rather than focusing solely on rehabilitation, OT helped patients reengage with meaningful roles and routines, shifting them from passive recipients of care to active participants. The provision of emotional support and social engagement was equally important (C4.2). The OT provided consistent presence, active listening, and emotional reassurance, particularly for socially isolated patients.

Contributions of the OT (Theme 5)

Participants perceived OTs’ role as adding distinct, practical, and preventive value to the home-based care team, addressing gaps in care related to safety, functionality, and caregiver support. The central contribution was the adaptation of the home environment (C5.1). The OT conducted in-home assessments to identify safety risks and barriers to independence, and recommended tailored modifications, ranging from furniture reorganization to the installation of assistive devices. These changes often resulted in visible improvements in safety, making them among the most valued aspects of OTs’ work. As the nurse manager emphasized, “Patients are often at home in poorly adapted spaces, and they begin to encounter physical barriers as they experience limitations.” Environmental factors are a key issue, and adaptations are often needed”.

Informal caregiver education was another critical area (C5.2). The OT provided family caregivers with hands-on, contextualized training on safe mobility support, task management, and ergonomic techniques. This support helped caregivers feel more confident and less overwhelmed, enabling them to become more effective care partners and enhance the sustainability of home-based care arrangements. The OT also played a key role in fall and risk prevention (C5.3), implementing proactive risk assessments and personalized strategies such as rearranging living spaces, introducing assistive tools, and coaching on safe movement. This preventive approach was valuable for frail and high-risk patients receiving home-based care, often addressing overlooked safety concerns. Finally, functional retraining and exercises (C5.4) formed a core component of the therapeutic domain. The OT developed individualized plans focused on IADLs and autonomy, tailored to the patient’s needs within their dwelling.

Structural limitations and challenges (Theme 6)

While the integration of OT into the home-based care team was well received, participants identified several systemic barriers that hindered its full implementation and long-term sustainability. These challenges encompassed issues of clarity, resourcing, and evaluation, and were deemed critical to consolidate the role.

A recurrent limitation was the absence of a clear patient profile definition (C6.1). PHC nurses and the GP reported a lack of standardized criteria for determining which patients should be referred to OT. This led to under-referral and inconsistent decision-making. As the OT noted, “Sometimes I had to explain informally how to detect the kinds of needs I could address because there were no clear criteria for referral.” The OT often had to informally guide colleagues on how to “detect the kinds of needs I could address.” Although some internal guidelines have gradually emerged, the process has remained inconsistent and largely dependent on individual clinicians. Concerns about human resources and sustainability (C6.2) were equally prominent. PHC nurses and the GP expressed uncertainty about the role’s future, highlighting the risk of losing progress if institutional commitment and funding were not secured.

Finally, the absence of indicators and evaluation (C6.3) emerged as a structural barrier to sustaining the OT’s role. Without formal metrics, teams relied on anecdotal evidence, making it challenging to demonstrate the effectiveness of the OT or justify investment. The nurse manager, GPs, and PHC nurses emphasized the need for an evaluation framework to capture outcomes related to function, caregiver burden, autonomy, and health care use.

Quantitative methods study results

Patient profile and OT interventions

A total of 248 patients, with a mean age of 88.2 years (SD = 7.3), were visited by the OT, and the majority were women (70.97%, 95% CI: 64.89%–76.54%). They had a high burden of chronic conditions, with a mean of 11.1 diseases (SD = 4.2); 77.8% (95% CI: 72.13%–82.83%) were labeled as chronic complex patients, and 10.1% (95% CI: 6.63%–14.52%) were labeled as patients with advanced chronic conditions. Social risk was identified in 44.4% of those assessed (n = 227), and 9.3% lived alone (n = 214). Cognitive impairment (Pfeiffer, n = 227) was identified in 55.2% of participants, with impairment presenting in 14.1%. Functional assessments indicated that 45.6% had severe or total dependency in basic ADLs, and among those assessed for IADLs (n = 151), 36.3% had moderate to total dependency. Regarding fall risk (n = 244), 43.2% reported at least one fall, and 4.0% had more than three. Patients received a mean of 3.55 OT visits (SD = 1.84), with 60.7% receiving 1–2 visits and 6.6% receiving more than six visits. Additionally, they received an average of 8.63 PHC nurse visits (SD = 11.07) and 2.97 GP visits (SD = 2.13). Table 3 shows all characteristics, and Table A1 in the Appendix reports the disease frequency among the patients visited.

Profile of occupational therapy interventions

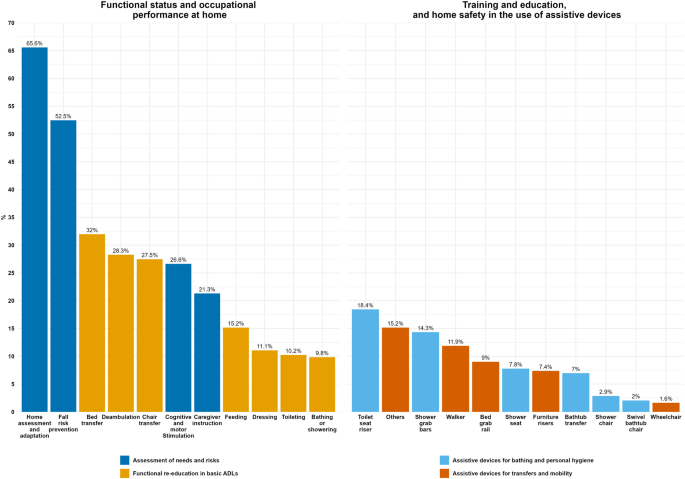

During home-based visits, the OT performed a broad range of interventions, primarily focusing on assessing functional needs and enhancing independence in daily living. The most frequently delivered occupational therapy interventions involved functional status and occupational performance assessment at home, with an emphasis on identifying needs and risks. Home assessments and environmental adaptations were performed in 65.6% of cases, followed by fall risk prevention (52.5%), cognitive and motor stimulation (26.6%), and caregiver instruction (21.3%). Regarding functional reeducation in basic ADLs, the most common interventions were bed transfers (32.0%), ambulation (28.3%), and chair transfers (27.5%). The other targeted activities included feeding (15.2%), dressing (11.1%), toileting (10.2%), and bathing/showering (9.8%).

Assistive devices for bathing and personal hygiene were commonly recommended, with the most frequently prescribed devices being toilet seat risers (18.4%) and shower grab bars (14.3%). Other devices included shower seats (7.8%), bathtub transfer boards (7.0%), shower chairs (2.9%), and swivel bathtub chairs (2.0%). The most frequently prescribed assistive devices for transfers and mobility were walkers (11.9%), bed grab rails (9.0%), and furniture risers (7.4%). Wheelchairs were prescribed in 1.6% of the cases, whereas other mobility-related devices accounted for 15.2%. The bar graphs in Fig. 1 display the activities in descending order according to the following two domains: functional status and occupational performance at home (left) and technical aids to support functional independence and home safety (right).

Activities conducted by the OTs during home-based care visits, categorized into two domains: Functional Status and Occupational Performance at Home (left) and training and education, and home safety in the use of assistive devices (right)

Association between functional profiles and the type of occupational therapy interventions

Patients with moderate or severe dependency received a higher number of activities focused on the assessment of needs and risks (median [IQR]: 2.0 [1.0–2.3] and 2.0 [1.0–2.0], respectively), compared with those with low or no dependency (median: 1.0, 95% CI: 0.0–1.3) and 0.5, 95% CI: 0.0–1.8, respectively; p = 0.005). No significant differences were observed in functional re-education activities (p = 0.17), the provision of assistive devices for bathing/personal hygiene (p = 0.78), or transfers and mobility (p = 0.05). Table 4 presents the analysis results.

When analyzed by patients’ fall history, no statistically significant differences were found in the number of activities provided across fall frequency groups for assessment or reeducation categories. However, the use of assistive devices for bathing and personal hygiene showed a modest increase among those with three or more falls (median: 1.0, 95% CI: 0.3–2.0) compared with those with no recorded falls (median: 0.0, 95% CI: 0.0–1.0; p = 0.05). No significant differences in the use of assistive devices for transfers and mobility were observed (p = 0.09). Table 5 presents all results.

link